|

Forest of Dean Central

Railway

The Forest of Dean is located

in that little triangle of land between the Severn and the Wye

as they approach their confluence just north of Bristol. It is

stuffed with various natural resources (such as coal, wood, iron

and limestone) as well as large animals (deer, boar, sheep and

suchlike). It has lots of trees and a reasonably large population

living in rather industrial-styled houses sat in the middle of

nowhere.

By 1900 this world was linked

to the rest of the universe by four railways. The Monmouth Tramroad,

later the Great Western Railway's Coleford Branch, ran steeply

downhill across the four miles from Coleford to Monmouth. The

Lydney and Lydbrook Tramway, which rapidly became the Severn

and Wye Railway, presented a fiercely independent network linking

the towns of Lydney, Coleford, Lydbrook and Cinderford (remaining

independent in spirit even after it sold out to the Great Western

and Midland railway companies). The Forest of Dean Tramway ran

from the port at Bullo, near Newnham, to Cinderford, becoming

the Forest of Dean Railway after takeover by the Great Western

and subsequently obtaining an extension out of the northern end

of the Forest, the last part of which was never opened.

Suggestions had been made

in the early years of the 19th century that this last route,

also known as the Bullo Pill Tramroad, should be linked to some

mines in the Moseley Green area (between the Severn and Wye and

Bullo Pill routes) with the Moseley Green and Tilting Mill Pond

Tramroad. This idyllically named little chord, one of the earliest

schemes to link the isolated valley of the Blackpool Brook with

everywhere else, was regretfully never built. Things might have

been rather different if it had been.

|

Instead, in 1832 a scheme arose

to build a tramway from Purton, on the banks of the Severn, through

a 600 yard tunnel and into the Forest near Blakeney with a general

target of the middle of the Forest via the Blackpool Brook. Construction

of the Purton Steam Carriage Road was begun before its Act of

Parliament was obtained, with an incline, a viaduct, part of

the arrow-straight tunnel under Nibley Hill (west of Blakeney)

and the northern end of the Lightmoor branch being completed

fairly promptly. The Bill was then postponed after the Severn

and Wye and the Forest of Dean Tramway pointed out that they

weren't so far apart really and the infrastructure was never

used; the incline was swept away by the South Wales Railway,

the tunnel has vanished under the A48 and the viaduct and the

Lightmoor branch survive. No effort was subsequently made by

the two tramways to serve the area which the proposed route had

intended to connect to the then-important port of Purton, Gloucestershire,

from where a ferry crossed the River Severn to the quay at Purton,

Gloucestershire. Nobody even seems to have been very excited

about reviving the Moseley Green and Tiliting Mill Pool Tramroad. |

|

|

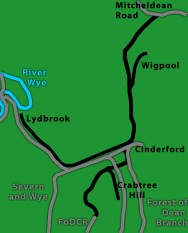

DFMU&PR in black, surviving railways

in grey, rivers blue, land green.

|

The next scheme of note to

propose running up the valley from Awre was the Dean Forest,

Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway - a lengthy, good quality

cross-country route which was placed before Parliament in 1853

and (as far as the Dean Forest elements were concerned) promptly rejected. Its aim was to carry iron (and, to a lesser

extent, coal) from the Forest to the ironworks at Merthyr Tydfil;

other railways would complete the route west of Pontypool. It

avoided all the tricky coastal bits of South Wales Railway (past

Purton and below Chepstow); they were replaced by a tunnel at

Howbeech, lengthy banks up to Coleford and a few nasty bends

(none of which really concerned promoters armed with reasonably

powerful 50mph locomotives). Unfortunately, like its predecessors,

it also involved competing with the Severn and Wye. |

The western and easy

half of the DFMU&PR proceeded as the Coleford, Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway,

which shut up the Severn and Wye and allowed the plan to proceed;

the line between Monmouth and Pontypool was

completed in 1857. The Coleford extension was completed to a

rather lower quality by the GWR in 1883, while the Severn and

Wye upgraded their tramway to provide a similarly tortuous route

to Coleford from the Severn and Wye mainline at Parkend. Beyond

Parkend, the 1853 scheme proposed a tunnel to pass under a hill

to Howbeech, from where the mainline was to continue to Awre,

with a branch from Howbeech to Foxes Bridge.

In due course some local

businessmen realised that this valley was not going to get a

link provided by outsiders any time soon, so they adopted the

section of the scheme which proposed to link Awre with Foxes

Bridge and made it the fourth and last railway company to open

shop in the Forest. Early financial problems delayed construction,

led to the contractor being paid in worthless bits of pink paper

which the railway described as its shares and prompted a decision

to leave the last 1½ miles up to Foxes Bridge for completion

later. Linking Awre Junction with New Fancy Colliery via Blakeney,

the new railway was completed at the same time as the Severn

and Wye Railway was converted from a tramroad into a proper railway

and began to gain from the increase in profits. Its decision

to build a new mineral loop, creating a lasso around the centre

of the forest, had much the same effect as a lasso when it opened

in 1872, pulling all traffic from collieries such as New Fancy

towards its port and junction in Lydney. Alas, the new railway

never stood a chance. Its pleas to the mighty Great Western Railway

to buy or bail it out largely fell on deaf (and broke) ears;

by the late 1870s it couldn't afford to print its own accounts

and the Great Western was working it on the basis that it was

there, so they might as well and might eventually get some money

back sometime.

The Central line was eventually

absorbed by the Great Western at the Grouping in 1923, demonstrating

that several railways which remained independent until then did

so because the phrase "damaged goods" was an understatement.

By then the Great Western was taking over a line with two miles

of operational railway plus a further two miles which pointed,

devoid of traffic, into a particularly isolated part of the Forest.

Those shareholders who wrote to the GWR after reading an article

in the Daily Express about a railway with no owner, enquiring

about the possibility that they might get paid something, were

told that they should contact the Directors and Officers of the

Railway who, the GWR kindly explained, had all resigned some

years previously (when it became apparent that the railway couldn't

afford to pay them). On Grouping Day the 54-year-old railway,

which had been the beneficiary of some £141,000 and had

generated a grand total of £32,000 over the years, passed

to the GWR free, gratis and for nothing in lieu of monies

owed to its new owner. (The Bank of England makes that £12.5million

in and £2.7million out; about £50,000 per annum in

earnings in modern money.) Its sorry remnants, worked with the

aid of a red flag, were treated rather well for a broken freebie

and survived until 1949.

The Severn and Wye Railway

stands amongst a very small selection of lines which successfully

killed a competitor and the grandly named Forest of Dean Central

Railway stands as one of an even smaller selection of routes

which obediently laid down and died. The rural nature of the

area, with minimal need to go to all the trouble of obliterating

railway structures to provide room for development, means that

the entire route can be followed even now, as seen in the pictures

below.

|

Awre Junction

|

Looking north-east towards

Gloucester, this April 2010 view of Awre Junction signal box

and the mainline shows just how much the place has declined -

or how little, given that it was never very busy. The station

was built for the new line and had platforms on the mainlines

with a couple of sidings and loops for shunting branch trains.

The branch never carried passenger trains and even at its peak

between 1868 and 1872 traffic seems to have run only on alternate

days. Most of the sidings were located on the derelict land beyond

the signal box with connections to the mainline at each end.

The station and the actual divergence of the trackbeds were behind

the camera.

The junction remained essentially

the same throughout the railway's career, carefully laid out

with no facing points on the mainline so trains from both directions

had to reverse onto the branch (which helped everyone get used

to the idea of going backwards, since there was no loop at Blakeney

and so from 1921 all trains had to be pushed up the branch).

With the closure of both station and branch in August 1959, the

site was cleared of all except the essential 1909-built signal

box, required to control the level crossing. In due course, like

the rail traffic, the signalling requirements shifted to Lydney

and the box has stood derelict next to the former mainline since

the 1970s. The simplified infrastructure also featured a facing crossover (plus a repositioned trailing one), on the back of which the location remained an important timing point for passing trains - though the crossovers were removed in the 1990s Awre still features in Working Timetable schedules to this day, but only as a useful check regarding punctuality of running.

Due to the Great Western

influence on this area, the South Wales Railway was constructed

to the Great Western's very own track gauge of 7'¼".

The Forest of Dean Central was also built to this gauge and the

main Forest of Dean Railway was converted to it shortly after

being acquired by the Great Western. When the Severn and Wye

was rebuilt it was also persuaded to lay its track to this gauge.

However, standardisation with the rest of the network in 1872

saw these lines all relaid to the normal 4'8½", leaving

a legacy of over-wide infrastructure and excess width between

the running lines on double track. |

|

Blakeney station

|

The line then runs attractively

up the comparatively wide and open valley to Blakeney, which

was the most important intermediate station on the branch. This

record was primarily achieved by being the only intermediate

station on the branch (the other points of note were mostly just

sidings) since Blakeney was not what might be called impressive.

As the line was goods-only, things like platforms where unnecessary;

since it was only an intermediate stop on a line which was only

used by one train per day (three days per week) it had no need

for a loop. Thus the trackwork consisted of the main line from

Awre to Howbeech, New Fancy and Foxes Bridge (which ran north

along the embankment to the right) and a single siding with crane

and loading platform (which ran behind the stone building and

connected at the Awre, or far, end of the site).

When the line's fortunes

went downhill this little site became its northern terminus.

In the continuing absence of a loop - the line's long term future

was evidently deemed to be bleak even in the 1920s - the locomotive

ran around its train at Awre and then propelled it to here. The

guards van - generally of the "Toad" variety - would

be deposited on the mainline and the wagons pushed into the siding.

Various local lorries collected the goods brought up on the train

and provided some for the return journey, for which the locomotive

would be at the front. The end of the line was denoted by a sleeper

tied across the rails on the embankment to the right, which is

tradition for doomed lines which aren't likely to be terminating

there for much longer.

A maximum speed of 10mph

was imposed over the line, probably because this was the maximum

for the ascending trains and so only half of the services using

the route could go faster in any case. The guard provided warnings

to the driver from his van at the front of the train with the

aid of a red flag and a horn. After the line fell into disuse

it remained in the Western Region's Working Timetable for some

years with empty columns and no booked trains. The track was

removed in early 1959. This picture, looking towards Awre, was taken in April 2010, towards the end of the site's years in industrial use; it is now a small housing estate. The stone building in the centre, then

partially hidden behind a tree and now kept in some crates at Norchard on the Dean Forest Railway pending re-erection somewhere, is original. |

|

Blakeney Viaduct

|

The village was also home

to the railway's two main engineering features - a pair of short

viaducts with the line's characteristic low arches, rather reminiscent

of Brunel's viaduct at Maidenhead. None of the underbridges along

the route left all that much headroom, averaging at about 10ft,

and consequently only one survives intact. This is the upper

one of the Blakeney pair, crossing a local road, the scenic route

to Parkend and Coleford, several drives and the local stream.

Although the arched sections still stand, the two girder spans

over the scenic route and the stream were demolished - along

with all of the smaller viaduct, which crossed the A48 Lydney

- Gloucester road - in April and May 1959.

The viaduct had not actually

been seriously used since a 1921 strike prompted the abandonment

of Howbeech Colliery and killed the Blakeney to Howbeech leg

of the line. Officially closed in 1932, the track was lifted

in 1940, leaving a stub of slightly less than two miles for the

occasional freight train. Until then trains could work to Howbeech

after a check of the decaying structures to ensure that they

would survive the experience.

Blakeney might have survived

longer had someone bitten the bullet and provided a passenger

service over the stub of the line. A stopping service from Gloucester

to Blakeney might not have survived Beeching but would have left

the Great Western with something more approaching a legacy for

their own line into the Forest. Instead, the last goods train

from the well-placed goods yard ran on Friday 29th July 1949

and Blakeney has not seen a train since. |

|

North of Blakeney

|

Once over the second viaduct

the railway passes through a short cutting and then heads up

the valley on a hillside ledge. The valley is obediently straight

for about quarter of a mile before it twists left and then sharply

right. The railway solves this problem by sweeping across the

valley and plunging through the hillside in the centre in a deep

cutting. With the closure of the line, the cutting has been filled

with rubble and is now impossible to spot at its northern end.

At the southern end, however, it can be distinguished as the

road passes over a deep ravine which is soon blocked by rubble.

The deep cuttings are one

of several things which mark this line out from the other railways

in the Dean, which were all built along the routes of earlier

tramways and so opted for fairly minimal earthworks, instead

utilising steep gradients and sharp bends. This new railway,

which does not use a former tramroad as a basis, went for more

sweeping curves, high embankments and deep cuttings. Gradients were more mixed - at this point, 2½ miles from Awre, it has already climbed about 40m from Awre Junction (averaging about 1-in-85, divided into sections of 1-in-69, 1-in-152, 1-in-182, 1-in-70 and 1-in-67 plus a level stretch through Blakeney station), before climbing another 50m in the next 2 miles to Howbeech (averaging about 1-in-70, on sections of 1-in-67, 1-in-100 and 1-in-58), which are all less of a struggle than the Severn & Wye's default of 1-in-40. The Severn and Wye,

Forest of Dean Railway and Coleford Railway all opted for tunnels

whenever they encountered a hill which they could not easily

go around and the Severn and Wye built an impressive viaduct

across the valley at Lydbrook. The impressive viaducts on this

line were rather low and not exceptionally long; where the line

has to cross over the valley in the distance it uses a high embankment.

There were no tunnels anywhere along its 6-mile route. |

|

Blakeney Kilns

|

The line emerged from its first major cutting into what we may as well call the Blackpool Brook Gorge

- nearly two miles of narrow winding valley with steep sides. The main road north from Blakeney comes alongside and the two transport routes cross the Brook together

on top of a single-arch culvert - seen in the upper picture, with skew portal and sizeable wing walls. (There is a kink in the middle of the culvert and the other end, presumably rebuilt at some point by the highways authorities to provide room for the road to be widened, is in a rather different and flatter style.)

Immediately north of this, below the railway and facing the brook, is a lime kiln - seen in the lower picture. The DFMU&PR liked running through the middle of existing industry, so probably thought that this was a useful feature of the landscape - the top of the kiln could be serviced directly from wagons. No siding was provided here, but in the circumstances of the traffic levels no siding was needed. In any event, the Forestry Commission's interpretation board reckons that the kiln went out of business shortly after the railway opened.

Kiln passed, the line swings briefly round a left-hand curve with the road on the inside of the bend at the same level and the brook on the outside of the bend a few feet lower down. The line then straightens up, the road curves onward to follow the valley, the brook passes under the railway by means of another large culvert and the line went into a further cutting on a rightwards curve. The south end of this cutting has now been filled in and the rest of it opened out into a quarry. Beyond the cutting, a shallow embankment led in a straight line up to the modern Forestry Commission Wenchford car park. |

|

Blackpool Bridge

|

The Wenchford car park has a seasonal northern exit route via a small overflow car park, which runs along the top of a shallow cutting wall (the Forestry Commission seems to have a thing against FoDCR cuttings) before crossing the Blackpool Brook using the railway's high embankment and considerable culvert. At the north end of this embankment is the railway's Blackpool Bridge over the ancient road from Soudley, which village had a station on the Forest of Dean Railway. While the

low arch - the only complete bridge left on the railway - may

be regarded as a bit of an obstruction, it does prevent large

vehicles from using this road and at least no longer has a gate

under it (one was around in the 1940s, although that may have

been the result of Home Guard exuberance). Built with a headroom

for which most companies would have opted for a girder construction,

the bridge does its best to suggest that the railway that it

carried between 1868 and 1921 (about a third of its life to date)

is still active. The only thing it lacks is the Railtrack sign

warning you that if you hit this bridge the safety of trains

may be at stake (a sign which has been affixed to a number of

other disused railway bridges) - oh, and an actual railway.

Having crossed the Soudley road, the railway continued to climb on its rising embankment round a curve to the west, taking it back towards the main road to Parkend. |

|

Stony Green

|

The main road was crossed at Stony Green by one of the FoDCR's low girder bridges, which is consequently no longer there. But the embankment on the south-east side is, and it offers an excellent viewpoint across the narrow valley. Passenger trains from Monmouth to Awre, had the line been built, would undoubtedly have been sedate things - but the scenery, from the vistas down the Wye Valley above Redbrook to the elevated views over the Valley Brook west of Coleford to this passage down the wooded gorge to Blakeney, would have been really quite something.

At some point before the railway opened - presumably when Mr Maller came along and turned the muddy track from Blakeney to Coleford into a turnpike road - the road at this point was realigned. It originally followed the riverbank to join the ancient road from Soudley on the east side of the railway, but this was abandoned and replaced by this alignment clinging to the hillside. As a result the railway had to build a bridge to cross it. If the original alignment had been retained the railway would have saved on a bridge, and all the road traffic this way would have had to dog-leg under the Blackpool Bridge instead. The DFMU&PR engineer proposed avoiding both this bridge and the next one by diverting the road to run slightly up the hill from the railway, which gives a basis for some interesting comparisons of relative costs of half-a-mile of land acquisition plus earthworks and road surface against building two small bridges.

Having crossed the road, the railway clung to the south hillside of the valley on an awkward ledge, looking down on the road and river, as it passed milepost 4 from Awre Junction. Two small quarries were passed (some of the foundations for the loading equipment survive) before the line pushed out from the south hillside and passed over road and river on a three-level crossing (the brook is stuck into some solidly-built stone-lined channels and culverts, the road crosses the culverts and the railway's girder bridge passed over the top). It then curved around the hill on the north side of the valley in a short, subsequently quarried and now partially infilled cutting before arriving at the transport complex at Howbeech. |

|

Howbeech Colliery & Wallsend Colliery

|

Not a right lot remains at Howbeech these days, except for a bit of flat ground and some more of the FoDCR's culverts. Under the DFMU&PR plans the approach cutting from Awre would have been a short tunnel (the engineer of that concern liked tunnels - he proposed six of them, on a line linking two points 24 miles apart as the crow flies) and around this flat area would have been the junction between the mainline to Monmouth and the branch to Foxes Bridge.

Though the mainline was never built, there was still a need for trackwork to accommodate the demands of four collieries - one adjacent to the railway (right-hand side of the upper picture), which was easy to serve with a couple of loops; one at the west end of the complex (now the grassy patch in the lower picture), which required a short siding across the road; one up the hill to the south (which was served with a short inclined plane, now a path); and one some distance to the north (served by a tramway, now gone). Names shown vary based on source - Ordnance Survey maps show the colliery across the road as Howbeech Colliery, while the GWR official survey says that the one up the hill to the south was Howbeech Colliery. The Ordnance Survey says that the colliery next to the sidings was Morse's Coal Level (disused by 1901) while the GWR says that this is Wallsend Colliery. Several other patches of mining in the vicinity are all generically described as Wallsend Coal Level. One assumes that when transport invoices were issued they were delivered to the correct firms.

The Howbeech area marked the top of a string of industries in a mile-long belt up the

Blackpool Brook valley. With fairly reliable streams to provide

power and a railway which initially wanted to go places and which

subsequently would almost pay you to provide it with traffic

this was a good area to start your heavy industry. Although initially

this just provided some additional traffic to supplement what

little was being produced by New Fancy, from 1872 the collieries

and quarries found themselves as the major source of traffic

for the line.

The quarries slowly slipped

out over the years - most of them had been quarrying back cutting

walls, inferring very light traffic since explosions are normally

discouraged around active railway lines for fear of hitting trains

or obstructing the running line, so scheduling them tends to

be very difficult. The collieries (between them) dutifully

supplied traffic for around 50 years until a miners' strike killed mining in the neighbourhood in 1921, taking the railway north of Blakeney with it. Thought was given to reviving mining in this neighbourhood by the new National Coal Board in the late 1940s, but the proposal was that the transport link would be provided by the Severn & Wye Mineral Loop. (This was an odd idea, because the S&W is some distance away and quite a lot higher and the tunnel at Moseley Green wasn't in the best of health even then. Of course, the logic depends a bit on where exactly the NCB envisaged sinking a shaft.)

Howbeech Colliery is not

as dead as the railway, however; a drift mine has now been dug

below the trackbed towards the older workings. A two-foot gauge

line allows mine trucks to be worked around the site. Produce

is presumably removed by lorry. |

|

West of Howbeech

|

Beyond Howbeech, the line

had only the briefest of careers. New Fancy colliery was the

only development to benefit from the final mile of track, and

then only for four years. The line left the Howbeech area in a cutting, curving gently around to the north, which was spanned by a bridge about two-thirds of the way along its length. This bridge has been removed and replaced by an embankment across the cutting, and both ends are now populated by trees. The cutting is typical of the FoDCR infrastructure - long, deep, slashing

through an arm of the hill and in a location where the other

Dean railways would have gone around the outside or built a tunnel.

The line was clearly intended to last and expensive earthworks

were constructed accordingly. But it was abandoned even before the final cycle of railways began to open.

At the north end of the cutting the line crossed the Blackpool Brook by way of another culvert. Though slightly modified, it appears that this structure has survived with an embankment scraped off and parapet walls added. It is on a straight line between two cuttings, and the stonework resembles other FoDCR culverts. Piling earth on top to about three feet high would produce a roughly broad-gauge embankment. Nowadays it carries the access road to Mallard's Pike car park. |

|

Mallard's Pike

|

The Forestry Commission has not left their access road to continue along the FoDCR trackbed - the trackbed heads into a shallow cutting, continuing its gentle curve to the north, while the access road loops around the outside of the hill (the Forestry Commission appears to have a thing against FoDCR cuttings). This cutting, drier and more walkable than the previous one, carries the line through a hillock adjacent

to Mallard's Pike lake and opens out to point across the car

park at the trackbed north (though the north end seems to have been used to bury the septic tanks for the car park toilets and has a certain odour). Were the line still open, it would

now be a minor tourist route - Mallard's Pike is one of the many

beauty spots in the Forest (when it isn't raining) with a new

"Go Ape!" climbing place and one end of the Forestry

Commission's cycle network. Yet this stretch of the line officially

closed in 1878, having never seen a passenger train (or indeed

the lake, which post-dates closure); the only vehicular access is now

by car or bicycle. Unlike many stretches of track around the

country, it is hard to envisage a scenario for this line which

would ensure that it was still operating today.

Mallard's Pike claims that,

while both mallards and pike are common in the lake, it is in

fact named after Mr. Maller and his turnpike road from Blakeney

to Coleford. Turnpikes were good quality roads maintained by

charging users a toll for travelling along them and arrived in

the 1750s along with the canals and the railways. Initially holding

a monopoly on passenger transport, the highly-profitable turnpike

network was taken by surprise when the railways realised that

they could make some money out of fast passenger trains - and

did so. The network was virtually extinct by 1850, barring a few minor exceptions like the toll road over the Cob in Porthmadog - although as Maller's Turnpike saw relatively little competition from a railway, it was presumably just a dead loss. |

|

New Fancy Junction

|

Clambering north from Mallard's

Pike, the line featured its final overbridge over a little Forest

track, but this has now been demolished, the track straightened

and the approach embankments removed. Shortly after we come to

one of those little idiosyncrasies of the Forest's rail network

- the junction which points in the wrong direction, imposed by

the gradient from Mallard's Pike and the following gradient to

New Fancy. Trains from Awre arrived on the left-hand path (then

a single track railway) and entered the loop/ pair of sidings

behind the camera. The train then headed off between the trees

along the grassy belt on the right towards New Fancy colliery.

Upon their return they simply reversed the process.

This method of working naturally

introduced a delay and so, when the Severn and Wye came along,

their sweet talking and the offer of access to Lydney Docks seem

to have persuaded the colliery management to change haulier.

The Severn and Wye Mineral Loop crossed the New Fancy branch

on the level, but this seems to have raised few concerns. Arguably

the Severn and Wye's methods for working two trains on the unsignalled

Mineral Loop (cross fingers and blame the signalman for the inevitable

accident) were far more worrying than a minor flat crossing anyway.

This was the quietest of

the extremities of the Forest's railways, with no proper roads

in the vicinity and the nearest house being located well over

a mile away. |

|

Looking north from the same

spot, we see the location of the turning sidings. About 300 yards

further up the line it crossed one of the many Forest tracks,

which is still there today. Barely 50 yards beyond that the Foresty

Commission's new road takes a sharp turn to the right, abandoning

the trackbed which has brought it from Mallard's Pike. The turn

marks the most northerly extent of the intrusion of this Great

Western-supported line into the Forest; what extends beyond is

a deserted and unused strip of land prepared for rail use but

never turned into a railway.

The Forest tracks, some

of which have names, are mostly run along very old roads which

linked mines, houses and general sections of woodland. This one

is unusual in being laid on a railway - the Forest of Dean Railway

is mostly derelict or footpaths and the Severn and Wye network

has almost entirely been converted into cycleway, except for

the bits which the Dean Forest Railway has re-opened. Although

the Forest is mostly open access this does not mean that the

tracks are actually public roads, being intended purely as bridleways

and a means for Forest staff and those who are lucky enough to

live at the end of one to get around. As footpaths go they are

very good, offering a solid surface which rarely vanishes into

a bramble bush or a bog, although one or two of those marked

on the current OS Explorer Map of the area (OL14) no longer exist

so a compass is still recommended. As cycleways they tend to

be rather sore on the bottom due to the uneven surface made of

medium-sized stones. As railways they are entirely useless; taking

a train along one tends to rapidly lead to a serious accident. |

|

Beyond...

|

Though the Forestry Commission's track leaves the trackbed around the site of the bufferstop (or sleeper tied to the rails) the formation itself peters out. For the next few hundred yards, up to the next ride, the trackbed looks very trackbed-y with only a few hints that it was never finished.

The main one is this culvert, which gives a good sense of how one goes about building culverts. The cuvert itself - the stone tube between the trackbed, with finished ends (now partly collapsed) to the arches - is complete, and the trackbed has been built on top. The rest of the portal, with parapets, facing and wingwalls, is mostly missing. The line on top, having run north-north-west past New Fancy, is now beginning a gently canted curve around the relatively broad valley floor to a north-westerly heading on a rising S&W-style gradient of 1-in-40. |

|

Central Bridge

|

In a most unusual move,

the Severn and Wye actually co-operated when its new mainline

was obliged to cross the authorised, if incomplete, Forest of

Dean Central Railway. It built three bridges in one embankment

- one over a still-unsurfaced Forest road, one over this railway

and one over the Blackpool Brook (which came off worst, with

an 8-inch high culvert). Unusual in that it rendered unnecessary

the railway that it crossed, this structure provided neither

company with any particular benefit and when British Rail lifted

the track on the Severn and Wye Mineral Loop in the 1950s it

took the bridge span with it.

The replacement structure,

made entirely of timber resting on the original abutments, was

built when the Forestry Commission turned most of the abandoned

stretches of the Severn and Wye network into cyclepaths. While

the line into Cinderford and the bottom end of the Mineral Loop

remain abandoned (the former has too many tracks slashing through

the trackbed and the latter passes through a collapsing tunnel),

the new transport network has attracted traffic levels far beyond

those obtained by the Severn and Wye Railway. Always known as

"Central Bridge", this span has even been marked as

such on the cycleway leaflets - though the pathside marker point is (to be pedantic) in the wrong place, and few will realise the insignificance

of what lies beneath the timber girder. |

|

And so the railway ended.

Looking north from the Severn and Wye's overbridge, we see what

work took place to extend the railway deeper into the forest

before the scheme was abandoned, heading up the valley towards

Speech House lake. Strangled by its smaller competitor, the Great

Western never ran a revenue earning train under this bridge.

The trackbed which was deemed by the Official Survey to have

been prepared for use ends at Ash Ride, which is marked by the

line of trees across the trackbed in the distance.

This is not the end of the

trackbed, although it is beyond the end of the track, so does

not constitute the end of the article. As this spot featured

one freight-only line crossing another freight-only line, there

isn't even the option of returning to civilisation in a railway

carriage, which means that you may as well stay on for the last

bit. There is a sort of nice feeling about exploring this last

stretch of the Forest of Dean Central line because you know that

you're seeing as much as anyone ever has seen; nobody was born

too late to travel on the "last ever" railtour out

here. (Equally it's a rather sad feeling that people went to

a lot of effort, spent a lot of money and got nothing for it.)

It is hard to take pictures of the line north of here, as it

is mostly overgrown with trees and is rather indistinct anyway.

In some respects, this means that it is the most fascinating

bit to explore. Other people may wish to stick with the bit south

of Mallard's Pike. Whatever your view, the only way to get back

to Awre from Central Bridge is - and always has been - to walk.

Sorry.

For the last mile the trackbed

consists of a flattened surface running through the trees (rather

literally, as a lot of them grow on it), visible only if you

really know what you're looking for. The last level crossing,

over Ash Ride and next to a small structure called "Reform

Bridge" (which carries a Forest track over Blackpool Brook),

is followed by a steadily widening flattened surface with the

brook to the left of ascending trains (not that there were any)

and a small bank to the right. This then crosses over a very

small culvert; the next stream north is obliged to cross the

trackbed on the level, and a few yards beyond that the level

surface apruptly ends in a two-foot-high bank. The slightly higher

land beyond has a more crumpled, natural feel to it for another

couple of dozen yards before it rises into the dam of Speech

House Lake (which post-dates the proposed route). |

|

Speech House Lake

|

The Forest's railways crop

up occasionally in various television programmes, but the Forest

of Dean Central probably scored highest when it appeared in BBC

One's show Merlin, which may perhaps make up for the fact

that not a frame of footage appears to have been taken of the

railway while it was alive. You wouldn't have noticed it, although

bits of the filming took place on the proposed route of the trackbed,

which ran through the current site of Speech House Lake. The

lake has been cast as Lake Avalon, in which role it has made

some convincing and well-performed appearances during the three

series (although arguably the role would have been better filled

by the larger Woorgreens Lake, just beyond the top end of the

railway, which has reeds, a more obvious island and a rather

entertaining backstory). The visible line of the railway ends

less inspiringly in a birch wood below the dam at the bottom

end.

There were two more level

crossings planned in close proximity for Forest tracks; the first

over the path now running along the lake's northern shore just

in front of the camera and the second over Spruce Ride, just

behind the camera. A further level crossing would have been required

about quarter of a mile further on. A few traces exist north

of the lake, heading up towards Foxes Bridge Colliery, making

it just possible to follow the former trackbed for the rest of

the way. There is a dry ditch running north from Spruce Ride

here which you keep to your right; eventually a second appears

on the left about ten feet from the first and this should be

kept to the left for the rest of the way, ignoring the first

one, which will eventually vanish. Two paths are crossed en

route; the first a dozen yards west of a sharp left bend

between two tall pine trees and the second at about the same

point as the accompanying stream. Eventually what was to be the

trackbed will apruptly burst back into the open; the ditch should

still be kept to your right as you battle the bracken. An embankment

which probably dates back to Purton Steam Carriage Road days

crosses the bog; the railway would then have passed under the

road and run a few yards through the trees to its northern terminus. |

|

Foxes Bridge

|

Unfortunately Foxes Bridge

was denied the opportunity to be served by all three of the Forest's

major rail networks; only the Severn and Wye and the Forest of

Dean lines were connected to that particular hole in the ground.

It had a beginning not unlike the Forest of Dean Central, going

to a great deal of expense and still not getting what it wanted.

Initial diggings at a site convenient for the Speech House ended

up producing only water, which is available in vast quantities

all over the Forest at no immediate expense to anyone and so

was of no use to the colliery owners.

The colliery therefore decided

to solve the problem by upping sticks and moving lock, stock

and barrel to Crabtree Hill, three-quarters of a mile to the

north of Speech House. Here they were able to benefit from the

much closer proximity of the Severn and Wye Mineral Loop and

the Forest of Dean Branch, both of which provided spurs to the

colliery. The Forest of Dean Central, meanwhile, found that it

had ended up in the paradox of the runner and the tortoise -

it was racing up the Forest towards the colliery, which in turn

was slowly moving away from the proposed northern terminus -

and decided that it couldn't afford the extension north of New

Fancy. It might have completed its trackbed later, but events

overtook it and the runner had to retire to Blakeney.

Meanwhile the tortoise went

the way of most of the Forest's collieries and its only claim

to fame now is that it marks the highest point on the main circle

of the Forestry Commission's cycle network, which deviates off

the Mineral Loop specially. A large isolated overgrown pond,

north of the Coleford to Ruspidge road and near the rather larger

Woorgreens Lake, now marks the top of Blackpool Brook, the northern

end of the line and the original colliery site. If you're lucky,

you may be able to get back to Awre from here without having

to walk the entire 6¾ mile route again. |

|

An extension was proposed in

the 1850s, when the line was still on the drawing board, to continue

to serve further collieries in the Forest. The Forest of Dean

Central, Lydbrook and Hereford, Ross & Gloucester Junction

Railways - perhaps the longest railway name ever proposed - was

not actually presented to Parliament and so the five-line network,

centred on Cinderford with lines to Foxes Bridge, Lydbrook and

the Hereford, Ross & Gloucester Railway, accompanied by three

branches of varying lengths, was never built as planned. The

Forest of Dean Railway's unopened northern extension settled

the Cinderford to Hereford, Ross & Gloucester bit, while

the Severn and Wye linked Cinderford with Lydbrook. The Forest

of Dean Central never reached Foxes Bridge and there was nothing

much to look at there, so that spur around Crabtree Hill was

unnecessary and remained unbuilt. Perhaps the proposed network's

most notable point was the mile-long Wigpool branch, to diverge

from the mainline a mile or so north of Cinderford at the town

of Drybrook, which planned to ascend out of the valley on a gradient

of 1-in-17.88. At 5.6%, had this rapidly rising spur been built

as a road it would have justified a warning sign; unfortunately

the Hopton Incline on the Cromford and High Peak Railway in Derbyshire

was steeper, at 1-in-14, so it wouldn't have become the steepest

length of railway worked by locomotives in Britain. |

|

There was also an effort

to connect the line up to the Severn Railway Bridge and the Forest

of Dean Branch by means of two short chords, both of which suffer

from straight line syndrome - an interesting condition whereby

some speculators decide that a route between point x and

point y would be useful and amuse themselves drawing a

series of straight lines over the gaps between existing railways.

The idea was that it would be possible to get Bristol from Bristol

to Hereford and thence to Northern England by a somewhat convoluted

route. You head north out of Bristol, cross the Severn Railway

Bridge, join the Forest of Dean Central just north of Awre and

follow it up to Blackpool Bridge before striking north across

country to pick up the Forest of Dean Branch by Blue Rock Tunnel,

a mile or so south of Cinderford. The Forest of Dean Branch can

then be followed to pick up the Hereford, Ross and Gloucester

Railway at Mitcheldean Road; another chord there allows through

running to Hereford. If necessary your train can then proceed

via various extremely minor lines through Central Wales. The

idea was presumably to compete with the dominant and somewhat

quicker Midland Railway. The Severn Tunnel killed the grand schemes

of this sort in this area by providing the option of using decent

double-track railways to get from Bristol to Hereford via South

Wales.

It is perhaps more interesting

to hypothesise as to what would have happened had the line been

built in the 1850s. The basic route would have been very much

the same, but if the Coleford, Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway's

earthworks are anything to go by then the line would have been

set out for double track. Possibly the second line would even

have been laid, as the route would have been a key part of a link from Merthyr Tydfil to the English cities. Around 1900 it would have plausibly resounded to Northamptonshire ironstone trains being lugged this way to Merthyr's ironworks. A passenger service would have been provided,

although it is unlikely that it would still be operating today. The need for freight links to Merthyr went with Merthyr's heavy industry (the Cyfarthfa works, the family of the owners of which had promoted the DFMU&PR, went in 1920, while the Dowlais works stopped significant ironmaking activity in the 1930s), and the lines from the Pontypool/ Abergavenny area to Merthyr closed in the 1950s so left no useful western outlet. The Merthyr area was lacking in flat land for modern spacious steelworks and once ironstone had to be imported from other areas steelworks at the tops of valleys became a nuisance to run, so the completion of the DFMU&PR seems unlikely to have changed Merthyr's fate.

The 1950s/ 1960s cuts essentially re-orientated railways in

this area to centre on hubs at Cardiff and Bristol with connections

to various provincial towns and cities in the area; this route

would have been deemed to have been in the business of linking

Cardiff with Gloucester and since there was another line which

fulfilled that function - the South Wales Railway via Chepstow

- this route would have been shut anyway unless Usk, Monmouth,

Coleford, Parkend and Blakeney provided a very good case for

its survival. As none of these places feature in the Beeching

Report, since they had already been stripped of their passenger

services, there is no particular reason to believe that this

well-aligned, if occasionally steeply-graded, route would have

survived to present tourists with its scenic attractions today.

However, the route which

became the Forest of Dean Central would probably have been more

successful and could have dented the fortunes of the Severn and

Wye (which would certainly have never run trains to Coleford).

Unfortunately the reality is that none of the Forest's railways

were well up in the success ratings and there is little reason

to assume that this abortive scheme would have been an exception

- unless it managed to market itself as the eastern end of a

railway between Swansea and Gloucester avoiding Cardiff and Newport,

which might have made it some money.

|

But we will never know and

instead the railway's history has a certain tragi-comic air.

Aside from the remains of the route pictured above, the only

other surviving bit of the Railway is Milepost 1¼, which

Dean Forest Railway has on display at Norchard - and very nice

it looks, although a slight error by the company who cast the

unusual mileposts means that the railway was recorded on all

of them as the "Central Forest of Dean Railway".

It would not be beyond the

will of people to re-open this route - it would merely be a question

as to whether anyone has the will to do so. Given the fact that

the northern terminus would be in the middle of a deep forest

well away from population centres, it is likely that the required

will is absent. Blakeney station has now been lost to housing, and a low bridge over the A48 is a tricky sell. Rail access to Mallard's Pike and Speech House Lake might have value, but it would be rail access without any obvious access point as Awre station is not a logical choice for re-opening and Blakeney is not an attractive tourist starting point. Foxes Bridge would make

a nice northern terminus if someone really fancies twisting the

line enough to get it up the east side of the lake (the south-east

side of the lake is above the surrounding land already so it

should be possible to scrape the railway around it and run the

first ever train along the trackbed beyond). Unusually, this

is a line where reopening it to broad gauge would probably more

historically accurate than re-opening it to standard - at least

over the top two miles.

As part of the Forest cycle route it would have attractions - "simply" extend the existing Mallard's Pike branch southwards, reinstating missing underbridges at a higher level, and then turning round at Blakeney to follow existing byways and bridlepaths up to the Dean Heritage Centre at Soudley, the existing rather lost bit of path past Blue Rock and ultimately to pick up existing paths at Ruspidge. It would make a rather long family cycle from Cannop, but the views are more glorious than the S&W mainline. |

Forest of Dean

Central Railway

Awre Junction to

Foxes Bridge Colliery: Incomplete

Awre Junction to

New Fancy Colliery: 1868-1872

Awre Junction to

Howbeach Colliery: 1868-1921

Awre Junction to

Blakeney: 1868-1949

|

The background image for

this page shows the Forest of Dean Central looking north from

its level crossing over the sidings at New Fancy towards the

ultimate terminus of the line. The bufferstops were located just

where the path turns away and the trackbed beyond there to Foxes

Bridge remains unused.

Isolated and quiet, the

northern terminus of the line contrasts starkly with the Cinderford

terminus of the Severn and Wye and Forest of Dean railways. On

a bright sunny day, like the one shown in August 2009, it is

a pleasant spot to linger a while on this now rural line. |

Unlike other railways featured

on this website, this railway tends to feature only in books,

magazines and folios of which it is not the main point of interest.

Aside from this webpage, there is an article by noted Forest

railway historian Ian Pope in Railway

Archive No. 12, a short bit in Middleton Press's Branch

Lines around Ross-on-Wye by Vic Mitchell and Keith Smith (don't

ask what it has to do with the network around Ross) and a few

pages in Forest of Dean Railways - Layouts and Illustrations.

This latter describes its history as "probably unique in

railway history" - not necessarily wholly true, as the Fort Augustus and Findhorn lines in Scotland similarly got strangled shortly after birth, but nonetheless its career was unusually brisk. H.W. Paar devotes two chapters

to the line in The Great Western Railway in Dean - A History

of the Railways of the Forest of Dean: Part Two (first edition

1965, second edition 1971). Only Paar and Pope manage pictures

of the portion of the line beyond Blakeney; Pope has more pictures

and maps, but Paar has a gradient profile and a decent bit on

the proposed tramroad. The Public Record Office holds the Official

Survey of the line under RAIL 274/84; it shares the volume with

the Forest of Dean branch from Newnham to Mitcheldean Road, which

was also never opened over its entire length (despite being completed).

The fact that the two surveys are bound together at least means

that you can't get them confused and order the wrong line. They

also have the "Absorbtion Papers" (Rail 258/229) which

consist of four large bundles of interesting sheets of paper

discussing the line's atrocious career. The various aborted schemes

can be found at the Gloucestershire Records Office.

__________

<<<Wye

Valley Railway<<<

>>>The

Main Line>>>

>>>Coleford,

Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway>>>

>>>Coleford

Branch>>>

<<<Railways

Department<<< |