The Monnow Valley

Railway

Monmouth - Skenfrith

- Pontrilas

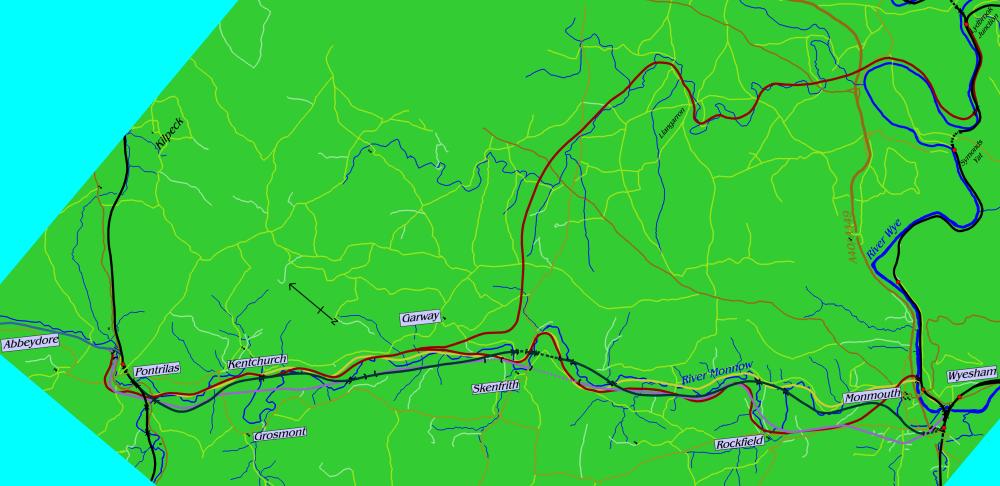

The 1860s scheme is the dark green line between

Monmouth and Pontrilas, while the 1883 one is represented by

a purple line. The dark red lines are the 1888 scheme and the

yellow line is the 1889 scheme. Primary roads are in red, secondary

roads in orange, minor roads in yellow, very minor ones in white,

other railways in black and rivers in blue. Any stations which

you may be able to pick out are shut.

The 1860s scheme is the dark green line between

Monmouth and Pontrilas, while the 1883 one is represented by

a purple line. The dark red lines are the 1888 scheme and the

yellow line is the 1889 scheme. Primary roads are in red, secondary

roads in orange, minor roads in yellow, very minor ones in white,

other railways in black and rivers in blue. Any stations which

you may be able to pick out are shut.

As railways go the MVR left

a great deal to be desired - the principal thing on the "To

organise" list being a railway. Two companies proposed links

between Monmouth and Pontrilas up the attractive Monnow Valley

and neither succeeded in organising anything much.

First up was an 1860s project,

which appears to have been principally driven by its contractor

Thomas Savin. It proposed a route with three tunnels - one at

Monmouth and two at Skenfrith - and nine major river crossings

- too many to list the locations of or, indeed, for any reasonable

railway to afford. It announced plans to work with the Coleford,

Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway - then the only railway serving

Monmouth - to develop what would later be known as Troy station

as the junction at the south end of the route. It would have

been a rather unusual junction, with at least three and possibly

four platforms built around lines bursting out of tunnels in

an impressive manner on the western side of the site and dropping

to a single freight-only line (climbing over a viaduct and across

the Wye to Wyesham Wharf) on the eastern side of the site. The

single-track line would have provided an outlet for Forest of

Dean traffic to the North - a long-running ambition of the era

- since at the Pontrilas end it was to form a junction with the

Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway.

Work began in 1866, shortly

after two more railways to Monmouth (from Ross to the north and

Chepstow to the south) had been approved, and the odds looked

rather good on Monmouth having four railways by the end of the

decade. However, Savin had been spending the previous few years

overstretching himself with heavy investments in his fleet of

railways, of which the Monnow Valley was a fairly typical example

- it ran through a hilly area of sparse population with lots

of expensive earthworks en route. Indeed, the only point

on which the Monnow Valley differed from its fellows was that

it was under 30 miles long. It therefore shouldn't have come

as too much of a surprise to too many people when Savin went

to the wall within weeks of beginning work on Monmouth's new

railway tunnel. The tunnel probably wasn't to blame for his bankruptcy

- a more likely cause is his other project, the Mid-Wales Railway,

which had just been completed at considerable expense to link

up various isolated bits of Wales where very few people lived

and industry was largely unknown.

Soon after any prospect of

recovering the works and continuing the project were destroyed

by the collapse of the Overend and Gurnley merchant bank - the

last run on a bank until Northern Rock in 2007 and brought on

by a crisis about the ability of its debtors to pay after a failed

claim against the Mid-Wales Railway - and the ensuing economic

recession, which also nearly killed the lines from Ross and Chepstow

into the bargain. The Wye Valley Railway's eventual arrival from

Chepstow was soon followed by bright ideas about the high probability

of recommencing work on the line, which probably didn't please

any of the three complete railways very much since their tidy

Monmouth terminus was still marred by the incomplete (but rather

large) hole in the wall of the approach road which was supposed

to have become a railway tunnel for the last attempt.

However, it was equally now

undeniable that a line from Monmouth to Pontrilas would make

a very useful outlet for Forest of Dean traffic to the North,

since the outlet which had ultimately been provided allowed trains

from the Severn and Wye Railway network in the Forest to join

the Ross and Monmouth Railway at Lydbrook - pointing south and

towards Monmouth, which wasn't exactly the direct outlet wanted.

An alternative was provided with a steeply-graded route between

Mitcheldean (on the cross-country line between Hereford and Gloucester)

and Cinderford (the northern nucleus of the Forest network) a

couple of years later, but that went on to show that just because

someone built a railway didn't mean that they were under any

obligation to call in the Board of Trade and obtain permission

to run trains over it. They could just leave it to rust away

instead. Which they did.

So the 1880s dawned with no

direct link from the Forest of Dean to the North - although since

the junctions at Lydney, Awre and Bullo all pointed in a vaguely

northerly direction, even if they were at the southern end of

the Forest, one does have to wonder why there had over the years

been so much fuss over it - and so a new project emerged. In

fact it emerged three times over the decade, with various developments

and alterations on each occasion which converted it from being

an upmarket through line to a twisting chord of no real importance.

It was to be built as part of a through line to Hay-on-Wye -

the Golden Valley Railway was planning to link Pontrilas with

Hay and thought that a southwards extension to Monmouth would

be a useful connection to help boost their railway's credentials.

(Their prospectus suggested that their line would form part of

a direct link between Liverpool and Bristol. The bulk of the

100-mile route was to single track, with steep gradients and

a maximum speed of 40mph. Bits of it hadn't been built yet.)

Hay was already served by

the Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway (another of Thomas Savin's

jobs). Done correctly, the cross-country line from Monmouth to

Hay could have given Hay some status as a railway junction, although

since Forest industry wasn't doing exceptionally well and there

was no industry or population to speak of en route there

was no reason as to why it should have particularly flourished.

In the event it never had the opportunity to flourish. The line

from Pontrilas to Hay was an unmitigated failure from opening

throughout in 1889 (it had managed to open part-way in 1881 and

then struggled to even afford a begging bowl to raise the cash

to cover the rest) and never found the money - despite its management

having the inclination - to extend to Monmouth. In 1898 all services

ceased - almost faster than a typical Golden Valley train

- although in 1901 - after three years out of commission - the

Great Western Railway reopened the route and ran it as a public

service. In summer 1935 trains were leaving Hay empty and passenger

loadings rarely scraped into double figures. It closed "for

the duration" (of the Second World War) in 1941 and was

eventually dismantled in 1957 after reopening was decided to

be unlikely.

The villages of Rockfield,

Skenfrith, Garway, Grosmont and Kentchurch therefore never got

their much hyped railway and instead got to watch on with interest

as Abbeydore, Bacton, Peterchurch and Dorstone went through the

unenjoyable experience of being served by a transport company

with barely sufficient funds to buy the next day's coal for the

locomotive. The railways mentioned in this story almost all proceeded

to close - the Severn and Wye began to vanish in 1929 and little

remained after 1956 (although the Dean Forest Railway has preserved

six miles); the Monmouth to Pontypool line mostly shut in 1955

and Monmouth lost all passenger trains when its other two branches

closed in 1959. The Hereford, Hay and Brecon closed in 1963 and

Pontrilas station closed in 1964, a few months after goods traffic

to Monmouth had ceased. The Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford

largely survives today.

The series of pictures below

follow the route proposed in the 1860s; below them is a sequence

on the 1880s lines.

|

Monmouth Troy

|

Thomas Savin's decision to

build a new tunnel for his line to leave Monmouth Troy station

through made a certain amount of sense; the tunnel that was already

there pointed in the wrong direction and another expensive tunnel

would have been required to allow the new line to pass out of

the Trothy valley used by the Pontypool line into the Monnow

valley to be used by the Pontrilas route. Monmouth Troy was less

than ten years old at the time and bore little resemblance to

the familiar station of the 20th century, which was largely the

result of the late 19th century modernisation of the Coleford,

Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway. Intriguingly, the only section

of the entire line to be built - this tunnel - is not on the

deposited plan, which infers that a cutting was planned instead.

The bore was intended to be

a short double track tunnel cutting through a low flank of the

Gibralter Rock and made a good point at which to start construction

of the line. Thus the Monnow Valley became the second railway

at Monmouth Troy station. Soon after it gained the indignity

of being placed on the list of "Incomplete Railways"

alongside such commercial successes as the Forest of Dean Central

Railway, although that at least got to operate a few trains over

the line that it built. The only use ever found for this tunnel

- which was only a score or so yards long, if that - was as the

station store. Its historic importance as the last piece of railway

infrastructure begun by Thomas Savin and the only feature of

the Monnow Valley Railway was probably largely ignored when squeezing

the station lorry around boxes to park it just inside the tunnel

portal at nights.

Later lorry designs were too

big to fit in the tunnel and it fell into disuse. In the 1970s

its proposed course was sliced into little pieces by the arrival

of the A449/A40 dual carriageway from Newport. At some point

around this time it was attractively sealed up completely with

a concrete wall. A 2002 housing development parked it squarely

in the back garden of a private house whose owners have attempted

to decorate the sulking arch with attractive garden plants. It

is at least no longer suffering the indignity of being used as

a storage space when it was intended to be a glorious transport

link, although at least in those days it had some purpose in

life.

Credit is due to the owners

of said private house for kindly allowing us to take the tunnel's

picture. It is the only piece of railway infrastructure you will

see on the line until we reach Pontrilas. |

|

West Monmouth

|

Once out of Monmouth Tunnel

the line climbed slowly around the back of Monmouth and crossed

the Rockfield Road just to the west of Monmouth's gated bridge.

The 1860s scheme proposed an easy gradient of 1-in-582 for this

stretch, with a 16ft high arched bridge. The ruling gradient

was a length of 1-in-123 between Monmouth and Rockfield - this

was to be a gently-graded line offering few challenges to even

the locomotives of the era.

Putting this into the context

of the photograph - which naturally shows no traces of the bridge

or associated property demolition since the plans never left

the proverbial drawing board - the gated bridge is behind the

white house to the right (it is now the No Through Road indicated

on the roundabout sign to the left). The railway would have passed

through the far end of the fine bit of 1960s architechture on

the far side of the roundabout, with the bridge suitably skewed

so that the right-hand abutment was a little closer to Rockfield.

None of the plans provide

station or junction layouts and instead make do with showing

where the single pair of rails were essentially planned to run.

Therefore it is not possible to conclusively say, based on the

initial plan, whether or not there would have been a station

around here. The answer is probably that there wouldn't have

been however; had it not been for the Ross and Monmouth's financial

problems, Monmouth would quite likely have had to make do with

Troy as the railhead until the 1930s. That does, however, mean

that in an incredibly roundabout and indirect way the Monnow

Valley may have improved Monmouth's transport links. |

|

Tregate Bridge

|

Open country, being open,

features few landmarks of note to identify precisely where a

railway would have run from a plan interested solely in the railway

and the surrounding 20 yards of land. Guesses can be made from

nearby farms and roads. It would seem to be a fairly good approximation

that if the railway had been built it would have come up from

Monmouth and Rockfield through the sparse line of trees in the

centre, straight through where the sheep are grazing, across

the road about where the picture was taken from and thence up

the valley towards Skenfrith.

The road from which the picture

was taken is that to the south-west of the "R" in "River

Monnow" on the map at the top of the page.

One of the striking things

about exploring unbuilt railways is that you are in essence seeing

the ground as it was before the railway was built. Had events

taken a different turn the sheep would probably not be grazing

on a level field but on the side of a slightly raised track.

The photograph would have been taken from a fine arch bridge

about 20ft off the ground. Instead we have an attractive and

largely untouched rural scene which has changed little over the

century since the line was proposed. |

|

East of Skenfrith

|

Skenfrith was to feature the

most impressive bits of infrastructure, including two tunnels,

so hopefully you'll forgive a lengthy pause here. Approaching

Skenfrith from the south-west, the Monnow turns to the north-east,

runs around a promontory, heads west into Skenfrith and then

turns north around another promontory, before returning to a

Pontrilas-bound course.

These sudden changes of direction

were too much for the original railway scheme, which planned

to skip all of them and bypass Skenfrith in the process with

the help of three river crossings and two tunnels in the space

of a mile. Few railways ever planned such intensity of major

engineering features (the closest in the Monmouth area was the

Hereford, Ross and Gloucester, which kept the bridges at least

a mile apart) and they can't have done much in the way of encouraging

the local bigger companies to build it.

This picture looks down the

valley towards Monmouth. The river can be seen winding around

the valley in a belt of trees. The railway would have approached

across the brown fields in the centre. It was then going to cross

the river, pass across the two green fields on the centre left

and enter the a short cutting on this side of the avenue of trees

climbing up the foreground field towards the farm on the right.

The cutting would have swiftly ended in the first and longer

of the line's two tunnels. The proposed styling of the tunnel

is unknown. |

|

Skenfrith

|

The hill through which the

longer Skenfrith Tunnel would have passed is crossed by a rather

minor lane, from which both the previous picture and this one

were taken. This picture looks towards Pontrilas; the river is

hidden behind the bank of trees across the centre. Skenfrith

is off to the left. The second promontory dominates the view;

Pontrilas is a few miles to the north behind it.

The railway would have emerged

from this hillside below the trees in the foreground, probably

in about the centre of this image. Almost immediately it would

have crossed the river on a short viaduct. After the river is

a narrow field; then comes the Skenfrith to Garway road; once

that was cross the railway would have plunged into the shorter

of its two tunnels.

The proposed location of Skenfrith

station is not marked. Here would have been the most convenient

point in relation to Skenfrith but the site would have been quite

tight and largely unsuitable. Stations were rarely built on bridges.

The other end of both tunnels is getting a little more remote

from Skenfrith, but to the north of the second tunnel and the

third river crossing would have been a possibility (albeit lacking

in road access, that area genuinely being all fields).

Of course, it is possible

that the promoters envisaged a through route with no intermediate

stops, but they were not very common on the whole and most railways

built in the 19th century provided stops at frequent intervals,

partly to appease the locals and partly to provide passing loops

(useful on single track lines). Stations purporting to serve

Skenfrith and Grosmont would therefore have ultimately been likely,

even if they were omitted from the map. |

|

West of Skenfrith

|

At the north end of the second

tunnel the line was to cross this attractive minor lane and then

immediately hurl itself out over the river, which is just on

the other side of the trees to the right. It was to have climbed

steadily all the way through the tunnels and over its three river

crossings; on the other bank of the river is a low promontory

pointing into the next meander which the railway would probably

have been able to pass over without having to cut into too deeply.

(The 1883 plans had the line staying on the valley floor and

a tunnel would therefore have been necessary to pass through

that meander. It would then have gone around the bottom of this

one, passing close to Skenfrith, and through a long tunnel to

pick up the Monnow again for the run down to Monmouth.)

All nine of the river crossings

on the 1860s plans were to feature single arch bridges with 60ft

spans, ranging between 10 and 20ft above river level. They would

have made a rather fine sight and it is something of a shame

that none were built for us to admire today. The low bridge across

this road that would also have been required would probably not

have been much of an impediment to the sort of traffic which

uses it.

The proposal with regards

to the tunnels was to drive cuttings into the hillsides until

they were 50ft deep and then begin boring the tunnels. Since

the hills are fairly perpendicular around here the resultant

cuttings would have been quite short. The cutting on departure

from Monmouth Troy was only expected to reach 46ft deep and so

would not require a tunnel. Why it was decided to bore one is

unclear. Since tunnels were rarely faced and lined until boring

was complete it is unlikely that the single tunnel portal built

for the line bears much resemblance to the planned appearance

for the tunnels up here (apart from the fact that it is a tunnel

portal and all tunnel portals have a certain familial resemblance). |

|

Grosmont for Kentchurch

|

The 1860s scheme was one of

these railways which saw a settlement of any particular size

and promptly bypassed it. This was, however, entirely because

the settlements weren't on a convenient through route between

Monmouth and Pontrilas - Skenfrith is at one extremity of

a meander and its fellow sizeable village in the area, Grosmont,

is at the top of a very big hill.

Therefore the railway cut

around the bottom of the hill and encountered the road from Grosmont

at Kentchurch, which is a very small hamlet on the north bank

of the Monnow with seven or eight houses and a pub. A farm on

the south bank has erected a fine line of covered pens along

a field boundary, roughly marking out where the railway would

have passed. Some road relevelling was anticipated.

It is not far from Grosmont

to Pontrilas and all four schemes had very similar ideas for

the last leg up the valley. On the final approach the Monnow

splits, with a tributary heading up into Pontrilas and the river

turning south towards Abergavenny. |

|

Pontrilas

|

The Newport, Abergavenny and

Hereford Railway has always approached Pontrilas from the south

unencumbered by junctions. It opened in 1854 and provided the

backbone for a number of branchlines winding off across country

in various directions between Newport and Hereford. The bottom

end of the line south of Pontypool was subsequently replaced

by the Pontypool, Caerleon and Newport (which is still in use

today, although it now serves Cwmbran rather than Caerleon) but

the route is otherwise largely intact. Although the intermediate

stations have all been heavily rationalised (and largely closed)

the line is still covered by semaphore signals. Every single

one of the branches along the way has closed and - with the exception

of the Coleford, Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway - lifted.

Thus it is statistically unlikely

that if the Monnow Valley Railway had been built it would still

be open today. (You may also wish to count the number of houses

in the pictures above too to get a rough idea of the sort of

passenger numbers that it might have obtained down the years.) |

Skenfrith returned to a proposed

railway map when Wells Owen and Elves, Engineers (of Westminster),

became involved in planning the South Wales and Forest of Dean

Junction Railway (generally abbreviated from hereon to the SW&FoDJR

to save space), which was to be submitted to Parliament in the

1877-8 session. It never actually was - perhaps someone pointed

out to the directors that a line with a fairly consistent gradient

of 1-in-40 in one direction or the other was not really practical

for heavy trains - so the plans for a line from Abergavenny to

Lydbrook via Skenfrith and Llangarron, with a branch to Ross-on-Wye,

were shelved. It was the sort of line for which the term "cross-country"

was invented. Its main aim was probably to allow Forest and Midlands

coal to be moved quickly and easily to Merthyr Tydfil and iron

and steel to be removed to the Midlands without requiring trains

to pass through Newport or wind around Hereford; the second half

of the journey, over the Heads of the Valleys line from Abergavenny

to Merthyr, wasn't really all that much better.

The 1880s saw the practically

bankrupt Golden Valley Railway decide that a Hay to Pontrilas

line was actually, on its own, going to be largely useless and

plans were put in hand for a link between Pontrilas and Monmouth.

The first scheme which was drawn up was presented to Parliament

during the 1883-4 session. This provided a series of differences

from the 1860s route:

- There was no connection into

Pontrilas station, so trains to Monmouth would have bypassed

the GWR station altogether by means of a 147-yard tunnel and

an avoiding line looping around the north and west sides of the

village;

- The straighter route would

require a second tunnel in the Kentchurch area;

- The line would have passed

around the outside of the main meander outside Skenfrith Castle,

allowing a decent station at Skenfrith and eliminating the shorter

Skenfrith Tunnel at the expense of building one to the north

of the village instead;

- The approach to Monmouth

would have resulted in a junction of remarkable size and expense,

with Troy station and the only extant earthworks being bypassed

to the north and the junction being built on the viaduct carrying

the Wye Valley Railway into Troy instead. Presumably the idea

was to connect with the GWR's Coleford Branch, then in the course

of construction.

- There were also various miscellaneous

realignments and gradient modificatios.

The Golden Valley was soon

reminded that its core aim was to link Hay and Pontrilas and

it had not actually yet achieved this. Its line petered out in

a field somewhere in rural Herefordshire, several miles short

of Hay. Such a railway should not be laying out plans to bore

1,684 yards of tunnel through lightly-populated low-industry

areas on the offchance that some through traffic might come its

way, so this one abandoned its expensive Monmouth scheme for

a bit and went back to raising money for lost causes.

In due course the 1887-8 Parliamentary

session saw the results of another survey of the area passed

up for authorisation after the Hay extension began to show some

signs of happening; there were four key differences from the

1860s route:

- The Pontrilas avoiding line,

as seen in 1883 and using a similar route, would allow Golden

Valley trains to pass Pontrilas without using Great Western metals

(although, unlike the 1883 plans, there would be a direct link

from Pontrilas station to the Monmouth line);

- The tunnels around Skenfrith

were replaced with a series of meanders, following the river

with the resultant tight curves;

- The rail network around Monmouth

was approached from the north, with a cutting under Monmouth

itself and the junction just north of May Hill station pointing

south, rather than using Troy station with an approach from the

west pointing east.

- A branch line from Garway

around Symonds Yat to Lydbrook was proposed, linking in to the

Severn and Wye network at Lydbrook Junction and featuring two

tunnels to make up for the loss of the ones around Skenfrith.

The GWR's Coleford Branch had been a flop due to its poor connection

with the Severn and Wye Railway at Coleford and the traffic which

would have been going that way was going via Lydbrook instead.

The engineers were the same

as the ones used by the SW&FoDJR, who appear to have taken

the opportunity to persuade the Golden Valley of the benefits

of using the surplus drawings for the Garway branch. There were

no practical benefits in terms of spare earthworks lying around

on the moors above Garway, since the SW&FoDJR hadn't actually

been incorporated and their only legacy was 16 pages of plans

detailing the proposed line. Some slight variations to the route

between Garway and Lydbrook were put in hand while the Skenfrith

to Abergavenny section and the Ross branch were both torn out

of the plans, but it was largely the 1877 route which the Golden

Valley incorporated as their proposed Railway No. 4 in the 1888

scheme.

Despite the curves and gradients,

the earthworks would remain quite impressive, with a viaduct

to cross the Ross and Monmouth Railway and the River Wye to the

east of Symonds Yat, several river crossings and a cutting under

Monmouth, which would have left a 50-foot deep trench under the

building which now houses the Nelson Museum. All-in-all the line

was going to cost a fortune to build and it is unlikely that

the Golden Valley managed to persuade many people to buy shares

in the route, particularly since it was already known that the

company was a basket case; certainly that would explain why the

Bill which was actually put before Parliament would appear to

have ditched the line between Garway and Lydbrook. (It also varied

the proposed route south of Skenfrith to largely run on the north

bank of the river.) The 1888-9 Parliamentary session featured

a new Golden Valley scheme which eliminated the Pontrilas avoiding

line as well, thereby reducing the scheme to a simple single

track chord with a siding to be installed at May Hill. This will

have had the benefit that the company could cut the amount it

was trying to raise in new share capital and the number of shares

that it was aiming to sell to raise this; once it had reached

the resulting much lower hurdle it could take out some large

loans to cover the remaining construction costs.

The lower hurdle doesn't seem

to have been reached either and the proposal was never heard

of again.

With the mainline from Pontrilas

to Monmouth largely covered above, the pictures below deal exclusively

with the proposed cross-country branchline from Garway down the

Garren Valley to pick up the Wye north of Symonds Yat, from where

the railway was to run to Lydbrook. The curvaceous line would

have passed through some very fine arable country and crossed

and re-crossed the Garren more times than is really decent. It

would also have annoyed pretty much every major landowner in

the area by slicing through their front gardens. Both versions

of the scheme will be considered, since there was not that much

difference between them.

|

Langstone Court

|

Langstone is home to a bridge,

a court (the country house variety) and not much else; the surrounding

landscape is typical of Herefordshire and its fertile nature

has clearly made the local landowner very rich (the staff get

rather comfortable houses adjacent to a large three-storey brick

manor house in expansive gardens). It was deemed to be the sort

of place that would like nothing better than a rail link; this

photo was taken from the middle of the proposed running line

at the point where it would have crossed the Langstone road.

Behind the camera to the left is Langstone Court; the green trees

running from the left into the centre of the view mark the Garren

Brook, which passes under Langstone Bridge. We are looking up

the line in the direction from which trains from Garway would

have appeared (due north; Garway itself is a few miles off to

the west. The railway was to meander around a bit).

Had the railway been built

and lasted into the 1930s, it would probably have obtained a

little wayside halt here. A full-blown station would have been

unlikely. The Golden Valley scheme was to run along the opposite

bank of the river to Langstone Court's front garden; the earlier

South Wales and Forest of Dean Junction Railway would have run

through the front garden and built its steeply-graded cross-country

line (aiming to carry lots of lovely black coal) straight across

the landowner's ornamental fish pond. Since the railway was never

built the front garden remains tidy and undesecrated, except

by a public footpath. |

|

Llangarron

|

Llangarron is the only

decent settlement along the route that the railway was to pass

through; since it is roughly halfway along the 13¾ mile

line between Garway and Lydbrook and three-quarters of the way

along the 24¾ mile line from Abergavenny to Lydbrook it

is probably a pretty good bet that the village was intended to

get a station (even though it isn't marked on the plans for either

scheme). The proposed course of the railway past the village

is still largely unobscured and, helpfully, the point where it

would have crossed the road linking Llangarron to points east

and north is marked by farm gates on both sides of said road.

This is the view looking north into the most likely station area.

The village church is off to the left; running trains through

the station on a Sunday morning would have brought a whole new

meaning to the old complaint that railways working such services

were indulging in "desecration of the Sabbath".

Llangarron station - had it

been built by either scheme - would have entailed levelling this

attractive patch of land and building a suitable station building

with platform, loop line and goods yard on it. The SW&FoDJR

was proposing running through the station on a 1-in-59 gradient,

rising towards Lydbrook, which would carry the railway over the

road on a 25ft wide 15ft high arched bridge. A similar structure

would probably have been built by the Golden Valley Railway had

they ever come this way - which they didn't, so the road past

the church is still nice and open with no obstructions, barring

the odd tree, for 16ft high lorries. |

|

Symonds Yat

|

The railway then planned

to pass down the Garren Valley to pick up the River Wye; it would

the follow the Wye around the east side of Symonds Yat, from

where this photograph was taken. The views would have been quite

spectacular; while the view of the Yat from the Ross and Monmouth

Railway was always somewhat spoilt by the fact that the railway

passes through the bottom in a short tunnel, the line around

the side would have offered a view straight up the side of the

cliff from the bottom of the valley.

The line was to appear in

this picture in the field on the left. It would pass through

the gap about halfway up the hedge. It was to remain about halfway

up the field for most of the inside of that meander, but the

railway would curve slightly more gradually than the river. The

result was that the line would neatly cross both the river and

the adjacent Ross and Monmouth Railway, landing on the other

bank around the start of the field in the upper left of the picture.

The Ross and Monmouth Railway

ran around the outside of this meander, passing along the bottom

edge of the line of trees in the centre before plunging into

the trees and, eventually, its tunnel. |

|

South of Lydbrook

|

The approach to Lydbrook was

to be made by running along the hillside a little above the Ross

and Monmouth Railway, with the Wye below the train to the west.

Largely this stretch was to be level, with a slight rise at 1-in-66

over a ridge and a similar fall down the other side into Lydbrook

Junction. The Ross and Monmouth rises into the station, so the

line from Llangarron merely had to run level around the hillside

until the line below it caught up.

This is the field seen in

the upper left of the previous picture. The simple earthworks

along this stretch would have required a ledge to be cut into

the hillside somewhere around the location of the brown cows

to the right of the picture. The mud track around the left is

the remains of the Ross and Monmouth Railway. It left behind

one centre of population - at Symonds Yat - plus the tunnel,

a few miles of basic trackbed alongside the river and no major

bridges.

The requirement for a three-arch

viaduct over the Wye would probably have ensured that the unbuilt

line wouldn't have lasted until 1959 even if the construction

teams eventually had rolled in around here. Since it was intended

to link into the Severn and Wye Railway's Lydbrook branch, which

closed in 1956 after years of declining traffic, it would probably

have gone at some point in the early 1950s. There was not due

to be a direct connection with the Ross and Monmouth, so through

trains to Ross were out of the question. |

Prospects for opening the

line are essentially nil. This website has certain connections

to Dr H. J. Nicholson, noted Templar historian, and consideration

was given to persuading her to back our evil scheme to capitalise

on Templar popularity and the ongoing search by certain sectors

of the world population for the Holy Grail by advertising Garway

as its hiding place and ferrying passengers from Pontrilas to

a station at Skenfrith for them to walk up to Garway and see

the church in which it is occasionally claimed to be hidden.

She explained that the Holy Grail doesn't exist and refused to

compromise her professional integrity. Since Holy Grail connections

are about the only way of screwing enough money out of people

to make the line turn in a profit (that and cooking the books,

although the experience of the Golden Valley suggests that some

serious cooking would be required), there is no real potential

of going for it as a commercial enterprise. A non-commercial

enterprise would be hard-put to find the cash to build a brand-new

line in rolling rural countryside. At the Monmouth end any effort

to access the original stations at Troy and May Hill to link

into the other trackbeds would cost a fortune and require mass

property demolition.

Basically, don't expect to

see a rail link between Monmouth and Pontrilas any time soon.

Its continued absence will give Skenfrith the unusual accolade

of being on five proposed railways yet never seeing the slighest

trace of a rail service.

|

The Monnow valley south of Kentchurch

is this page's background picture. It provides high quality agricultural

country but has never produced the sort of traffic which is conducive

to rail transport. This lack of heavy industry won't have helped

the proposals to build a railway this way, but if the Forest

had produced a bit more coal then building a railway out this

way to carry it might have become worthwhile, with the result

that the peaceful hills would have revertebrated to the sounds

of coal trains scrambling over the gradients. |

<<<Wye

Valley Railway<<<

>>>Ross

and Monmouth Railway>>>

<<<Railways

Department<<< |