|

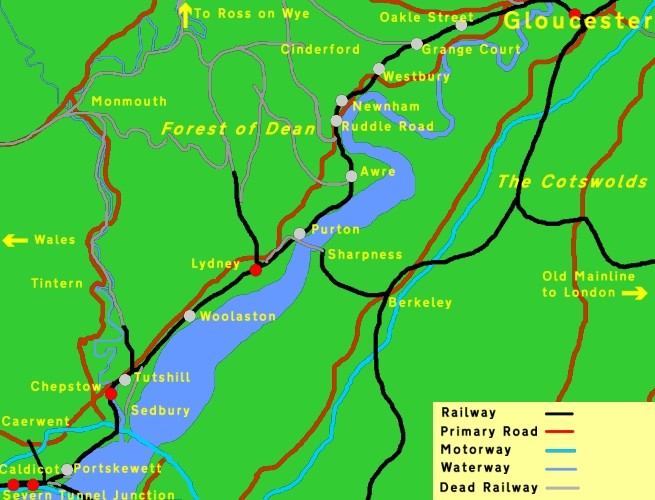

The Main Line

Severn Tunnel Junction

to Gloucester

Maybe "The Main Line"

is the wrong description for this route - it sees long distance

and heavy freight traffic, but that doesn't necessarily make

it a main line. It isn't often photographed, and there have never

really been calls for a total route modernisation. Many people

are almost oblivious to its presence.

It's part of the old route

from London to Cardiff, providing a roundabout, curvaceous line

which has, over the years, had nine junctions and thirteen stations.

The rest of the route ran from Gloucester to Swindon along a

line which sees one train each way per hour - alternating between

a Swindon to Cheltenham stopper and a London to Cheltenham intercity

working which both call at the same stations. These two lengths

of railway - which created a loop around the northern end of

the Severn Estuary and acted as the main line to London from

South Wales for 25 years - were superseded in 1886 by the Severn

Tunnel, which ingeniously runs directly under the Severn and

provides an almost dead straight route from Swindon to Severn

Tunnel Junction.

Gloucester to Severn Tunnel

Junction has since been something of a backwater and is served

by a stopping service with a clockface hourly path that doesn't

run every third hour combined with a semi-fast service calling

at Lydney and Chepstow to fill in the gaps.

|

The junctions saw lines branch

off to the following places (starting at Gloucester):

- Newent, Dymock, and Ledbury;

- Ross-on-Wye and Hereford;

- Cinderford (via Great Western

Railway);

- Blakeney;

- Coleford, Lydbrook, and Cinderford

(via Severn and Wye Railway) plus Sharpness and Berkeley (via

the Severn Railway Bridge);

- Beachley;

- Tintern and Monmouth;

- Portskewett pier (from which

ferries sailed to New Severn Passage, on the other bank of the

river);

- Sudbrook and the former Ministry

of Defence base at Caerwent (on opposite sides of the line).

This does not include Severn

Tunnel Junction itself, where the main line branches off to Patchway

and Bristol Parkway.

Then we have the stations

(again, from Gloucester):

- Oakle Street;

- Grange Court (for Ross-on-Wye

and Hereford);

- Westbury on Severn;

- Newnham (for Cinderford via

the GWR);

- Ruddle Road Halt;

- Awre Junction (for Blakeney);

- Gatcombe (in Purton);

- Lydney (for Coleford, Lydbrook,

Cinderford via the S&WR plus Sharpness and Berkeley);

- Woolaston;

- Tutshill Halt (formerly Chepstow

East, and at junction for Tintern and Monmouth);

- Chepstow (formerly Chepstow

West);

- Portskewett;

- Caldicot.

Talk about greedy. |

|

Below we have a table showing

pictures of this line and its supply of stations and junctions.

Most of the intermediate stations opened in 1850, and (except

for the Severn and Wye lines) the branches opened over the following

30 years. 1900 to 1955 saw a very slow decline, but then closures

came on thick and fast, and from 1990 until 1995 none of the

junctions for branch lines on the English bank saw any form of

traffic. The route is trying to revive itself now, although the

Severn and Wye (now the Dean Forest Railway) still seems determined

to outlive its younger neighbour, with trains to Lydney Junction

returning in 1995.

|

Severn Tunnel Junction

|

Here we see Severn Tunnel

Junction, looking east. For many years it was laid out with three

platforms through which trains ran in two directions. Up trains

(heading towards London) used the central island platform; those

using the Tunnel ran down Platform 3 to the left and those going

towards Gloucester ran down Platform 2 to the right. Down trains

(those heading away from London) all ran through Platform 1 (far

right); when a stopping train was occupying the platform there

was no means of letting anything overtake.

Consequently it was decided

to re-open Platform 4 (far left) so that Up trains for the tunnel

go through Platform 4, Down trains out of the tunnel use Platform

3, Up trains to Gloucester go through Platform 2 and Down trains

from Gloucester go through Platform 1. Work for this was carried

out over Christmas 2009, during which time the few through trains

to London ran via Hereford and Worcester. The station was also

given a bit of an overhaul, with new buildings, display screens,

a visible acknowledgement as to which platform was which (previously

only Platform 2 carried a number) and lots of CCTV cameras. Electrification

is the next upgrade; the previous Government promised it as a

good vote-winner and the new Government has got round to agreeing

to do something about it - not that it's really relevant to this

page, since the old mainline isn't due to benefit.

In the centre is the bay platform

for the Wye Valley line. Any proposal to re-instate the Wye Valley

line would probably not involve re-using this platform, but (despite

it being of no practical use) it has never been obliterated.

Instead it has been filled with rubbish, which is good for the

buddleia. The continued existence of the platform edging epitomises

the run-down nature of the station. The black sign on the lamppost

tells drivers of 2 and 3 car trains where to stop. The train

in Platform 4 is the 10:30 First Great Western service to Taunton. |

|

Looking the other way, we

see the west end of Platform 1. Hiding behind the pink-flowering

weeds to the left is the freight loop, which can be used by heavy

trains from Gloucester. The old station building for Platform

1 - which would have been awarded "Worst Welsh Station Building

(Large Bus Shelter)" award if such a prize existed and which

really should not be mourned - used to stand where the display

screen is now. Its replacement is the slightly more swish "Voyager"

shelter behind the lamppost (but that's still basic and a longer

walk from the footbridge). The lamp-post was turned around to

avoid damaging it while installing the new shelter and someone

forgot to turn the sign on it back afterwards, which means that

drivers of 2 and 3 car trains no longer know where to stop (although

4 car trains are still told to stop at the next lamp-post). The

island platform possesses the only original building surviving

- an unimpressive empty brick structure whose only function now

appears to be holding up a decorative board. On the far side

is the newly-rebuilt platform 4, along with the station car park.

This photograph was taken from the station footbridge, with the

road bridge in the background, on a fine summer morning in July

2010.

Dotted around the station

are bi-lingual station nameboards, with Welsh on top in green

and English underneath in black - for travellers going through

the Severn Tunnel, these are the last bi-lingual nameboards they'll

see. The Welsh name - "Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren" - is

a direct translation of the English, only it has been turned

around, so a direct translation back would read "Junction

Tunnel Severn". |

|

Caldicot

|

Caldicot station is the first

stop out of Severn Tunnel Junction, and a good telephoto lens

can show the platforms of Caldicot station clearly from the footbridge

at the junction. The station has two platforms and presents a

distinctly 1980s air. The buildings are so plain and simple that

there's nothing there to vandalise. Two trains pass through in

each direction for every three hours (with a minimal service

Sundays), so it's not too difficult to get a picture of this

station featuring no trains at all during a winter evening on

Sunday - which is when this picture was taken. |

|

Sudbrook Junction

|

Sudbrook Junction was provided

so that a siding could be laid from the main line to the new

pumping station at Sudbrook. The branch provided access to the

pumps at Sudbrook and allowed coal to be taken in to supply the

furnaces which provided steam to operate the pumps. However,

in 1961 the pumps went over to electric power and the branch

effectively fell out of use.

For some time it appears to

have struggled on, although by the 1990s it was being used exclusively

for stabling the Severn Tunnel Emergency Train. That then moved

to Severn Tunnel Junction, and the connection with the mainline

for the Sudbrook branch was lifted in the early 2000s.

On the other side of the line

was the junction for the line to MoD Caerwent, which headed off

across country to the left and the North, crossed the M4 (now

M48) and entered the military base at Caerwent. Opened in 1939,

it has been run down in recent years and the military presence

has declined to the degree that it has been used for cutting

up old railway vehicles. This traffic has also declined, and

the vehicles were increasingly brought in by road anyway, so

the line now looks somewhat disused, although the junction remains

in place (complete with crossover) and is still maintained. |

|

Sudbrook Branch

|

The pumps at Sudbrook were

built to drain the Severn Tunnel, then under construction, and

put the water in it into the Severn. It was a late move as initially

it was hoped that such apparatus would not be necessary - until

one day the tunnellers, during their routine digging, uncovered

the Great Spring, which proceeded to pour water into the tunnel

at a rate of 22,000,000 gallons per day. After the Welsh end

of the tunnel had filled with water in about two days (one mile

of mud still separated it from the English end) the pumps were

set up and, after two years, the tunnel was dry again. Happily

it has remained useable ever since.

The pumps therefore continued

to be rail served until their conversion to electric power and

the consequent use of the branch as a siding where the Severn

Tunnel Emergency Train was stored. This was moved to Severn Tunnel

Junction in the early 2000s and subsequently replaced by a pair

of single Diesel Multiple Unit cars built in 1960 and suitably

converted in 2003. All the vehicles associated with the Emergency

trains were placed on the market in late 2007 and sold "as

seen", with practically no mileage on the clock since conversion.

While the last trains to use

the branch have therefore been moved to train purgatory (being

dismantled at Cardiff to provide spares for the Cardiff Bay Shuttle

train, which is of the same design and similar vintage) the branch

itself is in its very own limbo waiting for someone to get around

to doing something with it. As most of it runs alongside the

narrow road through Sudbrook the logical one would be to use

it to widen the road; however, that would allow traffic to get

along it, which is currently out of fashion, and so it will remain

as it is for the forseeable future.

In the background of the picture,

showing the overgrown rails proceeding through Sudbrook, is the

impressive pump house. As the Severn Tunnel runs directly beneath

this line several websites specialising in maps and arial photos

have problems showing the tunnel and this branch, and often end

up suggesting that four IC125s plus several freights and stopping

trains traverse this route every hour, with the tunnel portal

being in the middle of the pumping station. |

|

Caerwent Branch

|

While the Sudbrook branch

heads in a fairly straight line away from the mainline, the Caerwent

line turns away sharply to the North, as seen here. Little has

used the branch in recent years, and it is starting to decay

a little.

Opened in 1939, it served

the new military base at Caerwent, which was expected to admit

practically all of its traffic by rail in those days, and so

wanted a good rail link. This line was therefore built across

the 1½ miles to Caerwent, with the first half of the route

mostly in a cutting and the second half principally on an embankment.

Apart from certain track alterations, particularly at the junction,

the only major change throughout its life came when the embankment

was sliced in half in 1966 as part of the construction works

for the M4 when it was extended across the Rivers Severn and

Wye into South Wales.

With the general reduction

in business at the base JT Landscapes expanded their scrap metal

business into cutting up old locomotives and rolling stock at

the rail-linked site. Immediately post-privatisation - from 1998

onwards - was a good time for this, with private operators -

particularly EWS - clearing out vast quantities of old stock.

The demise of the old Mk.1 stock on the Southern Region also

meant big money for scrap metal merchants and over 1000 vehicles

were reduced to scrap metal in two years. JT Landscapes also

got a few of the vehicles displaced from the West Coat Mainline

by the Pendolino programme and duly sliced two coaches and four

Class 87 electric locomotives before the owner found other things

to do with them. The coaches are now deemed to be in short supply

and the 28 spare 87s were sold to Bulgaria. Unfortunately in

2010 the Bulgarian company ran out of spare cash after only taking

delivery of 18 of them, leaving the other ten to face an uncomfortable

future at the hands of a South Yorkshire gas axe. (Only six went

to the gas axe, the other four ending up in Bulgaria anyway.)

No further fleets are slated for disposal now or at any point

in the near future so at the moment the site is empty, but when

vehicles are in residence they are generally visible from the

M48 motorway.

Therefore, while the MoD is

still keeping their track clear, there is no immediate demand

for it at present. |

|

Portskewett

|

The original station at Portskewett

opened in 1850 and lasted just over 13 years before being replaced

by the new one, half a mile closer to Gloucester and a mere 146

miles from London Paddington. This allowed it to become the junction

station for the Portskewett Pier branch - a task which it fulfilled

until the branch closed 23 years later in 1886. It was also briefly

the junction for Sudbrook from 1873 until 1878, when the Portskewett

to Sudbrook tramway was replaced by the Caldicot to Sudbrook

railway. The station slowly decayed to "wayside halt"

status despite being quite well-placed to serve Portskewett and

Sudbrook. The small, attractive station with gardens, buildings

and footbridge with ornate lamps was duly closed in 1964, although

the footbridge survives.

Portskewett itself is a small

place, mostly made up of modern houses, which looks like it wouldn't

mind a new station. Currently there is plenty of room for one,

but it's not on anyone's agenda at the moment. |

|

Portskewett Pier Branch

|

The Portskewett Pier branch

provided access to Portskewett Pier station, which was neatly

built quarter of a mile from Portskewett station on top of Portskewett

Pier. The pier was a large wooden structure which was built to

allow people to board ferries and be carried across the river

to New Passage Pier, which meant a much shorter journey time

to and from Bristol than that via Gloucester.

The branch had a short history.

Opened in 1864, it ran continuously until 1881, when the pier

caught fire. It was re-opened three weeks later and served for

a further five years until closure - it had been superseded by

the Severn Tunnel. The track was duly lifted and the pier demolished

without so much as a farewell special.

Despite the line having been

closed for over 120 years the trackbed is still remarkably intact,

with the picture looking down the last few yards of cutting towards

where the pier used to be. However, Monmouthshire County Council

wishes to use part for the cutting for dumping rubbish in. For

some reason the locals at Portskewett do not appreciate this

idea - soming about how it would involve big heavy lorries. |

|

Chepstow

|

Chepstow opened when the South

Wales Railway inaugrated services from Chepstow to Cardiff in

1850. The station was originally Chepstow West, due to there

being another station on the other bank of the river called Chepstow

East. Between the two there was the Wye and a coach service,

this being cheaper (and rather less impossible) than building

a bridge - a policy which continues to this day on the railways

when trying to deal with inconvenient things, like passengers.

On this occasion the problem

was solved by getting Isambard Kingdom Brunel - a notable engineer

of the time - to build a bridge across the Wye. Having built

it, he then tweaked his designs a bit and went off to build a

cheaper (and bigger) version at Saltash, on the border between

Devon and Cornwall, shortly before dying in 1859. The Saltash

bridge survives today, but the Chepstow one was demolished in

1960 and replaced with a stronger one - probably fair punishment

for driving Chepstow East and the connecting rail-replacement

bus out of business.

Chepstow station originally

had low platforms, but these were raised in the 1880s, following

complaints from Wye Valley travellers. The original buildings

- a neat matching pair, one on each platform - were duly jacked

up on heavy timbers and the platforms raised around them. In

1964 British Rail took it into their heads to demolish the Platform 1

building, but that on Platform 2 is original - albeit now with

no proper foundations.

After the First World War

the adjacent shipyards became the Government's National Shipyard

No. 1 - an interesting development which does not seem to have

lasted too long. The massive track network was being reduced

by 1930, and although the shipyards are still open (privately,

and quite limited) the railways have gone.

Today Chepstow is the first/last

station in Wales, looks rather run-down, and has lost its impressive

network of sidings (two headshunts and a bufferstop survive,

none of which can be seen in the lower picture as a Class 158

departs for Cardiff past the goods shed). Despite the miles of

railway which were laid 90 years ago, the current track layout

involves an up and a down line, with a single crossover for stone

trains off the Wye Valley Railway. The surviving building is

a cafe. The blue building to the right in the upper picture has

since been demolished and replaced with a small shelter similar

to those at Severn Tunnel Junction. In the gaps between trains

the station acts as an informal youth centre - passengers do

appear when a train is due, however, and the station can be quite

busy with people heading for the bright lights of Cardiff and

Newport. Currently it is the busiest of the three surviving intermediate

stations. |

|

Tutshill Halt

|

Once known as Chepstow East,

Tutshill was eventually re-opened as a halt at the east end of

Chepstow, near the former home of the Harry Potter author - although

not in the exact same spot as its predecessor, which was located

at the end of the cutting, halfway up a cliff overlooking the

Wye. Although the east side of Chepstow sounds like a useful

place for a commuter stop, circumstances conspired against it

- the walk to the main station is roughly 5 minutes, and the

rail journey is about one, so the Ministry of Transport is unlikely

to have seen much point in the extra stop. The Chepstow bypass

- the new A48 which goes across the Wye alongside the railway

rather than winding through the town's main gate and down the

High Street - slashes across the western end of the platforms

and cuts it off from Chepstow and Tutshill. More critically,

the halt had a fairly minimal service amounting only to the Wye

Valley trains, and therefore closed along with the rest of the

Wye Valley route in January 1959.

Little trace now remains of

the halt, and the fact that parking, disabled access, access

for anyone who doesn't like crossing 50 mph roads, and rebuilding

the platforms are all practically impossible ensures that it

is unlikely that trains will ever stop here again. |

|

Wye Valley Junction

|

On the opposite side of the

road bridge to Tutshill Halt, Wye Valley Junction marked

the point where trains to Monmouth branched off and headed north

into the Wye Valley. The junction was completed in 1876, and

services over the branch started the same year.

The Wye Valley line developed

over the years, but the junction was steadily rationalised. Initially

there were two tracks branching off (one up, one down); this

was reduced to a single track junction with a crossover connecting

the branch to the down main in 1936. A set of catch-points with

a sand-drag were provided instead to catch errant trains.

Following closure of the Wye

Valley line beyond Tintern Quarry in 1964 (passenger traffic

having already ceased in 1959), the junction was simplified again.

The points are now operated by a groundframe, with a ground signal

controlling movements off the branch. The crossover was moved

to Chepstow station, where it remains to this day.

Until 2007 the Wye Valley

Railway had the honour of being one of the last of the six branches

on the English section of the the line to retain its mainline

connection (between 1976 and 1990 it was the only one of the

six to carry traffic). The connection has now been removed at

some considerable expense and to no particular benefit. The branch

had not been used for at least 15 years, although the exact date

of the last train depends on which source you read - a common

problem with freight lines. |

|

Sedbury Junction

|

You would probably think that

Sedbury village does not look like the sort of place which could

justify a rail service with Chepstow and Tidenham stations so

nearby - and you would be right, as it couldn't. Instead, the

branch was opened to serve the shipyards at Beachley - a village

sandwiched between the Severn and the Wye. These shipyards -

the National Shipyard No. 2 - were built from 1917 to 1919, with

the railway being built to serve them. The yards were then closed

again in 1919 (imagine what the tabloid response would be today)

and the railway was then progressively shut down. Workmans' trains

were inaugrated in 1919 but withdrawn in 1920, with the junction

being removed in 1928. A loop line - there were originally two,

but the outer one was lifted in 1931 - survived until 1968, along

with a signal box.

The junction was complicated

by the existance of a lane to Sedbury which crosses the railway

on a bridge at this point - while the Wye Valley line (above

the mainline to the left) simply goes over it, this line wants

to be at the same level as the road, and spent about a third

of its life (1 year) passing under the road, leaving the mainline,

and heading south - this was revised for the remaining two years

of its life with the junction and signal box being on the east

side of the road, and the railway then climbed away and crossed

the road on a level crossing.

The site of the original junction

is still railway land, and is now used by a radio transmitter

for signalling between trains and the signal box at Newport.

The military retain a presence at Beachley to this day in the

form of an MoD base which seems to have opened at the same time,

but didn't justify a rail link on its own. |

|

Woolaston

|

Not lost to quite the same

degree is Woolaston station. It is clear that there was a station

here - it is shown on the 1960 map of the area as a closed station,

and the station building still survives, visible in its smart

coat of white paint. The station, which lasted for precisely

101 years 6 months (1st June 1853 to 1st December 1954) was never

a very major stop, with four trains each way each day halting

alongside the level crossing - which gave access to three fields

and the down platform. The village itself was half a mile away,

at the other end of Station Road, with the inhabitants mostly

living on the other side of the A48.

Woolaston can hardly have

been helped by the fact that, with a good telescope, you can

almost see the platforms of Lydney station, two miles away as

the crow flies (and as the train runs, since the marshes which

the railway is built on are dead flat and the railway is therefore

completely straight). In life it was a quiet wayside station;

in death it provides a constant barrage of noise as a kennels

and cattery, which ensures that Station Road bustles with the

kind of continuous traffic which it is unlikely to have ever

been subjected to during its lifetime. If you are heading from

Wales to Lydney with a bike, Woolaston station marks the point

where you should think about getting up to find it and wheel

it to a door. |

|

Lydney

|

Adjacent to the southern terminus

of the Dean Forest Railway, Lydney station is a fully-traditional

railway station - it is a mile from the town it purports to serve,

and is outside the area encircled by the by-pass. In a bid to

make up for this, various people have put lots of luxury housing

along the road to Lydney Docks, about half a mile away to the

south-east, and so Lydney station is actually near some houses.

The station's main building was on the

up side (right in upper picture), with a shelter on the down side (left in upper picture). The Up

building was eventually demolished and a small concrete shelter - now

garishly carrying Arriva Trains Wales colours - replaced it. The Down building

would appear to be original, albeit with the windows sealed up.

Originally the level crossing

in the distance was a rail over rail crossing, with the Severn

and Wye Railway line to the docks passing across the main line

on its way down from the Forest of Dean, which is to the right,

on its way to the Severn Estuary, which is to the left. After

the docks line closed the railway was converted into a road -

not terribly busy, but enough traffic comes this way to provide

a picturesque queue for the crossing gates.

The Severn and Wye Railway

arrived here before the mainline, as a tramway which eventually

found the money to upgrade to the broad gauge used on the mainline.

The mainline was then converted to standard gauge and, after

much grumbling, the Severn and Wye followed suit. By 1920 it

had a massive network in the Forest, with a main line to Cinderford,

a loop line which turned much of the northern half of the line

into a giant lasso around the centre of the Forest, and branches

to Lydbrook and Coleford. Passenger services beyond Lydney Town

ceased in 1929 and the network was steadily cut back over the

next 30 years until only stone trains to Whitecliff Quarry, near

Coleford, survived. These were then reduced until closure of

the network in 1976, which freed up the surviving Lydney to Parkend

section for preservation by the Dean Forest Railway Society.

The Severn and Wye is still

linked to the mainline - via a connection into the loops at the Gloucester

end of the station seen in the lower picture - and the link is used by the occasional

railtour. It is the last such link to survive on this section

of the route since the removal of the connection at Wye Valley

Junction. The station no longer has its own signal box however.

In its latter years the neat timber structure was a gate box

controlling this crossing and that at Awre, but in 2012 these

duties were transferred to a new signalling centre in Cardiff

and the box was demolished that December. |

|

Severn Railway Bridge

|

In many ways one of the greatest

engineering achievements of the Victorian era, the Severn Railway

Bridge spanned the River Severn at Sharpness from 1874 until

1960. It was a single track construction, built to carry Forest

of Dean coal to Sharpness Docks for export, and provide access

to the Midland Railway on the East bank of the river.

The Severn and Wye Railway

was struggling at this time, and quick construction of the bridge

might have staved off bankruptcy for a few more years. As it

was, the company rapidly found itself saddled with the even more

impoverished Severn Bridge Railway, which came with the sort

of astronomical maintenance costs which can be expected from

half-mile long bridges. The result was that the Severn and Wye

Railway began looking for buyers; after some blackmail, the Midland

Railway took over the southern end and the Severn Bridge, and

the Great Western Railway took over the section to the north

of Parkend. This mixed ownership lead to the railway network

retaining an individual flavour until it became part of the new

British Railways (Western Region) in January 1948.

The bridge remained upright

until a thick fog on the 24th October 1960. Two boats coming

up the river were tied together by crew members standing on the

bows (the front), in fog which was so thick that the captains

couldn't see that this had happened. The rising Severn tide swept

the vessels up the river past Sharpness Docks and straight into

pier 17, which disappeared in a large bang and a fireball - along

with the bows of the boats, five of the nine crewmembers, two

spans of the bridge, and the gasmain to Lydney.

Passenger services across

the river into Lydney Town station were promptly suspended, leaving

Lydney station on the mainline as the railhead. The inferno which

resulted from the accident as the fuel for the boats poured into

the river covered the whole distance from Lydney to Sharpness

and made escape very difficult. Fortunately the sport was on

the radio, so the track maintenance team were hiding in the Severn

Bridge signal box rather than patrolling the bridge.

Although at the time work

was being done to strengthen the bridge, it was never rebuilt

and a second strike on pier 21 two years later saw the decision

taken to demolish the crossing. Two contractors were bankrupted

by the job and it was ultimately never completed, with the support

for the swing bridge over the canal and approach viaduct at the

Sharpness end remaining intact to this day.

The occasional noise is made

about re-instating it, although it reality it remains a virtually

impossible pipe dream. More likely is the return of rail services

to each end - the railway is still intact into Sharpness and

re-opening could be achieved very cheaply. The other side, where

Severn Bridge station stands at the end of the embankment, is

of vague interest to the Dean Forest Railway, although the line

ran a little close to the modern Lydney bypass.

The upper photograph looks

up the west bank. The mainline curves into a bank of trees to

the left where the bridge once left its embankment to stride

across the river, roughly where a mudflat now runs into the tidal

estuary. The lower picture, from a road in the village of Purton,

looks across the Severn towards the faint grey smudge marking

the eastern approach viaduct and swing bridge support. |

|

Gatcombe

|

Gatcombe station was a typical

railway station in that it was in Purton. To reflect the fact

that Gatcombe itself is a half a mile away, it also carried the

name Purton Passage, and was located just above the slipway from

which the ferry would cross the river to Purton. The fact that

two places on opposite banks of the river are called Purton suggests

that it was quite easy to get across the river once - the ferry

is now long gone however, and the fact that Purton (Gloucestershire)

is about twenty road miles from Purton (Gloucestershire) is merely

a cause for confusion.

Gatcombe station (which was

precisely 130½ miles from London Paddington via Gloucester

- the milepost was halfway down the platform) opened with the

line in 1850 along with Gatcombe Goods, which was back up the

line at milepost 130 in Gatcombe itself. It was a simple two-platform

affair, probably with small wooden buildings and low platforms,

which does not appear to have been terribly successful. Unlike

many stations and branch lines in the country, its closure cannot

be blamed on Dr. Beeching, whose recommendations were published

94 years after this station was closed and demolished in favour

of Awre in 1869. Curiously the walk from Gatcombe to Awre Junction

is less strenuous than the one from Gatcombe station to the village

which it purported to serve. Gatcombe Goods (one siding and a

crossover) had a similar lifespan, with its traffic being handled

by Blakeney instead. This probably means that Gatcombe Goods

was built to handle Blakeney's freight traffic.

Purton was also due to play

host to a tramway which would have climbed up the hill from Purton

Pill and then run in a level sort of manner up the valley and

across farmland to somewhere. Only a short three-arch viaduct

which crosses the road into Purton was built, with the result

that there is a very effective 200 year-old block on vehicles

more than 15 feet tall approaching the village from the east. |

|

Awre Junction

|

Awre [pronounced Orr]

was not the most important junction on the route; if anything,

it was one of the bottom two. In the mid-19th Century, rail services

to the centre of the Forest of Dean were somewhat lacking, and

so a new railway - the Forest of Dean Central Railway - was promoted

to run from the mainline at Awre Junction, through Blakeney and

on to the collieries north of Mallard's Pike - a lake in the

depths of the Forest. There was also a bridge over the mainline

for a branch down to the Brims Pill on the banks of the Severn

- although they forgot to open that bit, the embankment is still

visible. Awre station was opened with the new branch line in

1869 and provided a slightly better passenger service to Blakeney

and Awre. Blakeney also got a convenient, if rather rubbish,

goods service from the branch line, which never saw a passenger

train.

The response of the Severn

and Wye Railway was to build the Severn and Wye Mineral Loop.

Leaving the Severn and Wye at Tufts Junction, on todays Dean

Forest Railway south of Whitecroft, it headed northwards past

Mallards Pike to rejoin the Severn and Wye at Drybrook Road station,

near Cinderford. Trains which ran up the entire loop would ultimately

end up facing back towards Lydney, due to the design of the junctions.

The Forest of Dean Central

tried to compete, but failed. The whole line was open for 10

years, but in 1878 it was officially reduced to only serving

some sidings in a particularly quiet part of the Forest. The

Severn and Wye did give it a bridge to allow it to access the

area beyond New Fancy colliery, but otherwise had actually eliminated

the threat from its smaller competitor as soon as it opened its

own line.

By the Grouping in 1923 much

of the route was disused, and from then until 1949 Blakeney was

the terminus, after which the line remained technically open

for a further ten years, prior to full closure in 1959. The junction

station was closed to passengers at the same time.

Although the route is still

clearly visible throughout, Awre Junction has long since been

flattened, with just the level crossing, the ruins of the Station

Master's house and the signal box surviving. How long the signal

box will remain for - or how long the house will remain visible

through the ivy - is debatable.

The box was retained to control

the adjacent level crossing, which is a full barrier affair with

flashing lights, sirens, and fast trains. Modern CCTV technology

means that the crossing can be controlled from elsewhere, so

the honour moved to Lydney in 1974 with the aid of some bright

floodlights for after the Sun's bedtime. Consequently the box

has been closed, and the nameboard removed, but it remains intact,

albeit slightly vandalised - its survival probably being helped

by the 24-hour security which is a must here, and therefore will

help prevent vandalism. Control of the crossing passed on to

Cardiff in 2012 and Lydney was promptly relieved of its box.

There is a longer article

on the Forest of Dean Central Railway here. |

|

Bullo Junction

|

Bullo is a curious name. Home

to Bullo Pill, it was also the junction for the Forest of Dean

Railway. It ran north from here towards Cinderford, serving the

many collieries and ironworks along the way, and eventually deigned

to offer a passenger service.

It is debatable as to whether

this line or the Severn and Wye was the more successful. This

route, which was ultimately entirely owned by the Great Western,

had the smaller route mileage and also never opened its northern

extension - a long branch line from Cinderford to Mitcheldean

Road on the Hereford, Ross and Gloucester Railway, with two tunnels

and steep gradients. It was completed in 1874 - the year after

the Severn and Wye began work on their own Lydbrook branch, which

gave access to the Ross and Monmouth Railway - albeit in a way

which forced northbound trains to run-around at the junction.

Rather than compete, the Great Western forgot about their line,

and left the route to rot. Part of the line was subsequently

used for passengers services, and a further half mile was used

to serve a quarry. The northernmost tunnel was never used by

Great Western trains, although the Admiralty subsequently used

it for missile storage. Following the Second World War, the line

was cut back, with passenger services ceasing in the 1950s alongside

the demise of most of the collieries along the route. Traffic

finally ceased on the 1st August 1967. The junction cannot be

viewed from public roads or footpaths and the best way to appreciate

it is to pass through the overgrown site - once home to an engine

shed, water tower and several sidings - on the train.

The route has a large supply

of trivia in its history, with the southernmost (Haie Hill) tunnel

causing several problems due to it being two-thirds of a mile

long on a steep uphill gradient with no ventilation shafts. Ridiculously

long trains of 100 wagons or more were hauled through by small

tank engines until one fireman ended up being carried out of

the smoke-filled hole on a stretcher. After this crews refused

to work the line with more than 40 wagons, much to the annoyance

of the railway company. During the early 1960s, Dr. Beeching

recommended closure of a number of railways around the country;

when a lorry crashed into the bridge over the A48 near Bullo

it was suggested locally that Beeching had been driving the lorry

at the time. The bridge was rebuilt and survived for three more

years before closure. There are no plans to re-instate this route. |

|

Ruddle Road Crossing Halt

|

Ruddle Road Halt was a short-lived

affair. It opened when a passenger service from Newnham to Cinderford

was launched in 1907. It is unclear what traffic it was expecting

which would not be better served by Newnham station, which had

mod-cons like local population, a waiting room (rather than a

hut) and through trains to Gloucester. The lack of traffic was

noticed during the First World War, before anyone had photographed

the halt, and it shut in the 1917 round of closures. It was demolished

in 1920, but did get to feature on an Ordnance Survey map from

about that time.

The design was very simple

- two wooden platforms, staggered so that there was one platform

on each side of the bridge (whichever direction you approach

said bridge from, the footpath up to the platform is on your

left). The bridge is one of several where what was once the South

Wales Railway crosses what is now the A48 on a stone arch which

is too low for modern requirements. Consequently large vehicles

are encouraged to go down the centre lane under the highest point

of the arch; larger vehicles are encouraged not to go beyond

Blakeney, as between there and Gloucester there are a series

of these bridges, all at about 14ft high.

Despite being abandoned for

90 years, the approach paths are still quite healthy - particularly

the westbound one, which can be followed up to the railway. This

picture was taken from the north side of the bridge. |

|

Newnham

|

Newnham opened with

the main line to serve the village of Newnham, but it rapidly

became the junction station for the Forest of Dean branch. It

was soon realised, however, that if the branch was to be opened

up to passenger trains there would be certain operational problems

at the two platform station as the branch train would terminate

on a through platform and hold up the traffic while the locomotive

ran around.

Eventually the station was

rebuilt with a bay platform on the south side, allowing branch

trains to terminate clear of the mainline. "Railmotors"

were introduced at the same time, running to Drybrook in the

north of the Forest. Railmotors were wooden bodied coaches with

a cab at each end and a boiler fitted just behind one cab, allowing

them to travel around, literally, under their own steam. This

eradicated the need for the loco to run around, so there was

no need for a loop. The railway had recently been converted from

broad gauge to standard gauge, which meant that there was plenty

of room for the extra platform when it was added in 1907.

Newnham is a small town with

a large clock tower by the A48 to give it a busy feel and the

station was not far from the centre, so the rail service will

have seemed fairly secure. The branch railmotors were replaced

by the Great Western's "push-pull" system (see Oliver

and Isabel in the Thomas the Tank Engine books - a tank

engine pulled a single coach up the valley and pushed it back

down) in the 1930s, and the branch closed to passengers in 1958,

although the bay had been falling into disuse long before then,

as trains began to run straight through to Gloucester - a sign

that British Railways was beginning to appreciate the need to

carry passengers with as few changes of train as possible. It

was not enough, however, to save either the branch or the station.

Trains have not stopped at

Newnham since November 1964, except when held at signals. Sufficient

room remains, however, to re-instate the station - maybe one

day. |

|

Westbury-on-Severn Halt

|

Next was Westbury-on-Severn

- a small halt which lasted for 31 years, one month and one day

before closure on the 10th of August 1959. Being an insignificant

little halt (rather than an insignificant little station) it

had no goods facilities. Instead, it had two basic wooden platforms

with a small galvinised metal shelter halfway along each, along

with a couple of station nameboards and some lights. It was located

between two bridges- the first carried the railway over the A48,

and the second carried the railway over the Blaisdon road.

Westbury-on-Severn is part

of a larger conurbation of various houses and areas of woodland.

The halt was only 1½ miles from the larger station at

Grange Court, which was also easily accessible from the village

- this may well have sealed its fate.

The photograph was taken from

an adjacent hillock. Behind the trees in the centre was the halt.

The far bridge, also hidden behind the trees to the left, crosses

the A48. |

|

Grange Court

|

Grange Court was junction

for Mitcheldean, Lea, Ross-on-Wye and Hereford - a spendid four

platform affair (two on the left and two on the right, the centre

pair being an island platform). Both routes were intended as

through lines to South Wales - that to the right being the mainline

to Swansea via Chepstow and Cardiff, while that to the left was

the mainline to Swansea via Hereford and Brecon.

The Hereford route was helpfully

built as single track, somewhat limiting its ability to attract

the traffic required to justify its many bridges and tunnels,

so the line closed during the Beeching era in 1964. Grange Court

was principally a junction station, and therefore there were

no nearby towns or sizeable villages, resulting in it following

its branch line into the history books in the same year. Its

pride as an intercity junction was somewhat spoilt by the payroll,

which in typical minor rural junction style featured a cat -

not that the cat got much choice on what it spent the pay on

(catfood from the corner shop mostly).

The loop lines remained intact,

but in 2004 Network Rail expressed an interest in removing excess

sets of points along the Severn Tunnel Junction to Gloucester

line. After funny noises were made at Lydney, it was pointed

out by the Dean Forest Railway (who wanted to keep their loops

and the associated mainline connection, thank you very much)

that there were two loops at Grange Court lying around doing

nothing. Eventually in 2010 they were disconnected from the mainline

and the crossovers removed, but the signal at the East end of

the Up loop is still on, glowing red at any trains which manage

to end up in front of it.

A curious little feature of

how this route was built means that Grange Court was a junction

between three railway companies - the Hereford, Ross and Gloucester

from Hereford, the South Wales from Chepstow and the Gloucester

and Dean Forest from here to Gloucester. It is doubtful as to

whether the passengers ever noticed this, since all three railways

were worked by the Great Western from the outset. |

|

Oakle Street

|

The last station before Gloucester

was that at Oakle Street. The small station was surrounded by

small villages, and the station took its name from the nearest

- the village of Oakle Street, which appears to be named after

the road. The nearest two villages of any size are Churcham and

Minsterworth (curiously both named after Christian buildings

of worship) which provided enough business to encourage the station

to open with the railway in 1851, but not enough to save it from

early closure four and a half years later in March 1856.

This was not the end for Oakle

Street, however, and it re-opened in October 1870 to passenger

and goods traffic. Things seemed to have remained healthy until

1953, when the signal box closed, with the replacement groundframe

being locked in and out of use by Grange Court signal box. Goods

traffic ceased altogether in August 1963, although passenger

services struggled on for a further 14 months before the station

closed forever in 1964.

The site has now been cleared.

It is hard to believe that there ever was a stop here as trains

clatter up the straight from Grange Court at 75mph on their way

to Gloucester. |

|

Over Junction

|

The last junction before Gloucester

was that for Newent, Dymock, and Ledbury. It was the archetypal

minor cross-country branch line, running for about twenty miles

through the middle of nowhere, and receiving the usual minimal

service.

Although an attractive line

(all minor closed branch lines are attractive according to their

sweet rose-tinted obituaries), the railway was not frequented

by enthusiast specials, or indeed by passengers, who were all

notable, even on the last day, by their absence. The railway

therefore closed as part of the 1959 round of cuts, and nobody

outside its immediate area appears to have been particularly

distressed that the 1885-opened railway was no longer providing

its apparently unnecessary service to the community.

The junction was as far east

as possible while staying on the west bank of the Severn. It

was a fairly simple affair with two tracks crossing the river

and heading off towards Severn Tunnel Junction while two other

tracks turned north, rapidly dropped to one, and wound off into

the countryside. Nowadays a signal sits in the middle of the

branch line, in the distance beyond the bridge. On the other

bank of the Severn, where the lines to the docks once branched

off, a trailing crossover now connects the two tracks of the

mainline with men in orange jackets looking at it thoughtfully. |

|

Gloucester Central

|

Gloucester Central station

was home to one of the more notable points where railway passengers

of the 19th century were inconvenienced due to some railway politics

and excessive displays of engineering genius. When George Stephenson

began building successful railway locomotives he built them to

work on his local railways, where the rails were 4ft 8½

inches apart. This rapidly became standard for all railways which

were built by British engineers or engineers influenced by Britain

- in other words, most of the world. Mr Odd-One-Out was better

known as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who thought that the traditional

track gauge (distance between the rails) was inadequate - and

so when the Great Western Railway opened in 1836 it was to a

new 7'¼" broad gauge. (It was not entirely illogical.

When the Great Eastern Railway was formed its first task was

to resolve problems caused by Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex each

having their own track gauge of around 5'.)

This was fine until railways

began to meet up and the most notorious example of this was at

Gloucester. This was the lowest easy crossing point on the River

Severn, so when the Birmingham and Gloucester and the Bristol

and Gloucester arrived virtually simultaneously they naturally

built a joint station pointing at South Wales. This required

a reversal for through Birmingham to Bristol traffic, which was

fine since it made changing locomotives easier - at least, it

would once the two railways had agreed which one would have to

convert to match the other's track gauge. The result was an interesting

picture entitled "The Break of Gauge At Gloucester",

with all the mail, the passengers, their children, their animals,

their luggage, their porters, their kitchen sinks, etc., trying

to get from one train to the other - and the standard gauge stock

was also noticably smaller.

The east-west extensions to

South Wales and Swindon were built to the broad gauge, but the

two north-south concerns were purchased by the Midland Railway

who converted the Bristol and Gloucester to standard gauge. Once

east-west operations had passed to the Great Western the break

of gauge was made less obvious by the Midland upping sticks to

its own through station at Eastgate, forcing passengers to engage

in such a lengthy walk to change trains that they didn't notice

the track gauge.

Broad gauge was scrapped locally

in 1872, resolving track problems for goods trains and leaving one easily noticable oddity on

the Gloucester - Severn Tunnel Junction route, among others,

in that the tracks are further apart than usual - about 10 feet,

rather than 6. The problem of two stations remained until 1972,

when British Rail and Gloucestershire Council came up with a

solution. BR could close Eastgate station, and Gloucestershire

Council could say that they'd asked them to do it due to the

excessive traffic in Gloucester being held up on the five level

crossings on the two-mile loop.

Although Eastgate was the

superior station from the operations point of view, it shut in

1972 and was replaced by a new road. The traffic is as bad as

ever, but the long-distance Bristol to Birmingham trains use

the avoiding line and do not stop at Gloucester, as this would

require them to turn around and go back out of the station the

way they came in. Instead, they stop at Cheltenham. Gloucester

- with its one train per hour to London, one per hour to Weston

Super-Mare, two per hour to Newport, and four per hour to Cheltenham

- tries to pretend that it doesn't care.

The yard at the east end of

the station became home to Cotswold Rail - a loco-hire company

and tour operator - until they went bankrupt in 2009. Antique

diesel traction in the area is now provided by Colas Rail and

Devon and Cornwall Railways - the latter offering the Class 56

seen in the upper picture squatting on a through road preparing

to head for South Wales. Few passenger trains now start here

so the west end bay (platform 3) to the right is largely used

for stabling stock. The lower picture looks from the other end

of Platform 2 late at night, with Platform 4 off to the left. |

|

Following the closure of Eastgate

station BR came up with another great idea - they closed what

is now known as Platform 4, which allowed them to remove the

footbridge. Of course, this left them with inadequate platform

space, so they put Gloucester Central into the record books by

building Platform One.

This picture was taken from

one end of this great platform. What you can see in this picture,

stretching into the far distance, is not all Platform 1. Just

after the red lights and at the other end of the teminating train

it turns into Platform 2, which has all the main buildings on

it. Most trains to and from Cheltenham use Platform 1 - it probably

saves about 5 minutes of journey time. In exchange, First Class

passengers on expresses turning back here are subjected to a

ten minute walk to the main buildings. First Class passengers

for the stopping service towards Newport used to have to walk

down to Platform 3, which is at the other end of Platform 2.

In total, Platforms 1 and 2 are 602.6 metres long - about a third

of a mile, which is nearly long enough for three full High Speed

Train sets and means that they comfortably hold the record for

the longest continuous platform face in the country. On the lamppost

at the very end of Platform 1 is a sign pointing to the "Way

Out" - the only exit is in the main station building - quarter

of a mile away!

Very kindly, the HST services

from London to Cheltenham have taken to turning back in Platform

2, thereby making the walk rather shorter. One of them can been

seen in the far distance. |

|

The current passenger

service is provided by four fleets of trains, although only two

put in regular appearances. The Arriva Trains Wales fleet principally

consists of trains built in the the 1980s and early 1990s, while

the (also Arriva-operated) Cross Country fleet is made up of

1990s stock. |

|

When in the 1980s it was decided

to replace the 1950s Diesel Multiple Unit fleet BR decided to

be clever and came up with two options - a cheap Leyland bus

pretending to be a train and a modernised, highly-expensive version

of the Southern Region's long-distance semi-fast diesel units.

The former failed to win any prizes for reliability and the latter

failed to win any orders, so after the two ideas had been mixed

with some ideas from their predecessors the Sprinter fleet was

born.

Unfortunately someone decided

that the bus pretending to be a train was too good an idea to

drop, although it took five prototypes, a trial fleet and four

years to produce a working design (unlike the Sprinters, which

took four trial units and six months). The result was the Pacers,

or Classes 142, 143 and 144; although the last of these tends

to stick to the North-East of England, 142s and 143s are a mainstay

of Valley Lines services radiating from Cardiff. Occasionally

one escapes onto a longer-distance working and this 142 is seen

at Lydney. Usually they handle the Sunday services. To be fair

to them, the decent track out here means that they ride well

and the wide bodyshells and big windows give them a spacious

air. |

|

The Sprinter fleet developed

somewhat over the years - the prototypes were two three-car sets

with no corridor connections on the unit ends, while the initial

production batch were two-car sets similarly devoid of doors

at the ends of the units (although they were now too short to

work single-handed on most routes, requiring twice as many units

to work the services and for them to be provided with two guards.

An excellent economy by the Treasury there. Both problems were

largely solved by hoping that the overcrowding would get rid

of the excess third of passengers).

The Class 150/2 units were

obligingly fitted with large doors bunged into the fronts of

the cabs to allow passengers and crews to move between sets.

Cardiff held out for a large allocation when the fleet was built

but progressively lost almost all of them over the years. Recently

various bundles have been drifting back and Arriva enthusiastically

painted them all in turquoise and cream in the hope that this

would ensure that they stayed here. Five duly ended up on short-term

hire to First Great Western. This one didn't; instead it is seen

on the first train of the day one fine September day at Lydney. |

|

The Class 158 "Express

Sprinter" fleet began arriving in 1989, with the first units

being allocated to Scotland. They were 90mph units and fitted

with air conditioning - although someone knew that it wouldn't

work and gave them emergency "hopper" windows too.

Initially South Wales's longer-distance Sprinters came in the

form of all 35 Class 155 "Super Sprinter" units, but

these had some reliability problems and eventually ended up being

rather cut up over it.

With the two-car 155s reduced

to single-car 153s and despatched to rural branchlines all over

the country, the 158s found their way to South Wales and the

Severn Tunnel Junction to Gloucester line. They also suffered

minor reliability problems and the gases in their air-conditioning

systems were subsequently banned for being bad for the environment,

but they have settled down to being a good fleet. Privatisation

saw the entire Wales and West fleet get a nice refurbishment

which was so good that hardly any of them have been touched since.

Arriva's 158 fleet is now based at Machynlleth and used on Cambrian

Line duties, so they are a bit rare down here these days but

pop by occasionally. This one is seen from a public foot crossing

at Bullo, heading down towards Cardiff (the only one of these

five pictures showing a train going in that direction). |

|

Some evolution of the Express

Sprinter design followed in the run-up to privatisation, resulting

in a fleet known as the "Turbos" being built for London

commuter services. After privatisation the new owners of the

former BR engineering division developed the design some more,

resulting in the Turbostar.

Two-car sets were soon to

be seen on Midland Mainline stopping trains; although a bit rattly,

they looked good and had nice big windows, so passengers flocked

to use them and they were increased to three cars. Then Midland

Mainline went back to the builder and bought some bigger trains,

the design having evolved into the Voyager in the meantime, and

the Turbostars passed to Central Trains. After re-franchising

they ended up with Cross Country, which has repainted them all

into a maroon and silver livery which rather suits them (accompanied

with an interior refurbishment which cleared out the worst of

the rattles). They work between Cardiff and Birmingham and don't

bother to stop between Newport and Gloucester, so when seen at

Severn Tunnel Junction the sixth member of the fleet was doing

about 75mph as it roared along in a happy Turbostar manner. |

|

Freight traffic continues

to make up a sizeable portion of the stuff trundling between

Severn Tunnel Junction and Gloucester, although there isn't as

much as there used to be and it is now all through traffic, with

no sources of income en route. The bulk of business now

consists of steel from Port Talbot (east of Swansea) and Tremorfa

(in the Cardiff Docks area) with some oil from Milford Haven

(the far west of Wales).

These freight trains are mostly

hauled by locomotives operated by the former English, Welsh and

Scottish Railway (or EWS, an American-owned firm) but this company

has been bought out and is now called DB Schenker (owned by Deustche

Bahn, the German State Railway). EWS traditionally worked everything

along here with Class 60s, but decided that all of them seemed

to look rather grumpy about something and the last couple of

years have seen almost all workings pass to newer, North American-built

Class 66s. The 107th example of this vaguely optimistic-looking

design is seen yinging through Chepstow on its way up the line

with a steel train. |

Notably the line bypasses

or skirts round most intermediate population centres. Prior to

construction commencing an alternative route was proposed as

the Chepstow, Forest of Dean and Gloucester Junction Railway,

which would have passed through the middle of Chepstow (sweeping

away the Tourist Information Centre outside the castle and wrecking

the view of said castle from the old road bridge), up the following

hillside in a tunnel and then run along the hillside about half

a mile inland of the current route. Four tunnels were to be built,

rather than the one required for this line (at Newnham - there

is also now one at Chepstow which was built for the benefit of

the A48), but otherwise the earthworks weren't to be much more

difficult. This scheme would have run north of St Mary's Church,

Lydney, rather than well to the south, the cliff section past

Purton and Gatcombe would have been replaced with an inland route

through Blakeney and a sweeping curve would have carried the

railway into Westbury-on-Severn rather than north of it. Apart

from the tricky passage through Chepstow, it was probably the

superior of the two routes from the point of view of its users

- though the tunnels would have made it more expensive to build

and more of a pig to work.

Instead we have this line

- poorly served and with future plans which are somewhat doubtful.

Resignalling is planned, as is giving Chepstow a half-hourly

service from Cardiff. Nice developments which are not currently

on the agenda would include re-opening Portskewett and Newnham

stations - connecting this with re-opening a couple of the branches

would be fun too (out of nine junctions, six have completely

gone, one has lost its pointwork and two are there but rarely

used). Don't expect anything other than the resignalling to happen

before 2020.

Electrification is not being

planned yet, so it should cease to be the Severn Tunnel diversionary

route once electrification of the mainline through the tunnel

is complete (presumably buses will be used instead). There is

a campaign to improve train services along the route so that

they actually offer an hourly service. This may happen if a few

more trains can be found (don't hold your breath - the current

fleet of Sprinter units would have to be augmented with more

Sprinter units and Sprinter units are incredibly prized where

they work already); meanwhile, there will continue to be slight

puzzlement in the upper echelons of railway management that one

of the most poorly-served double-track lines in the country is

proving to be so successful.

|

The background picture is

rather appropriate for this line, since it shows the railway

with rather hilly land on one side and a rather wide river on

the other. This was the attractive site of Gatcombe goods siding,

seen here looking towards Gloucester. Gatcombe used to be a port

of some renown but the arrival of the railway involved building

a viaduct across the mouth of the stream, rendering the port

inaccessible. Now trains swoosh past at speed, while a public

footpath allows access over the running lines to the riverbank

where locals moor their boats.

It is something of a shame

that this railway down the Severn Estuary simply isn't advertised,

but it does mean that new passengers are all the more surprised

as the train carries them past its scenic splendour - particularly

along this riverbank section between Lydney and Awre. |

For more information on

this line, try Gloucester

to Newport (Vic Mitchell and Keith Smith, Middleton Press),

which is about the only readily-available book to cover the whole

route. Other information has been gleaned from the many books

on the various branchlines along the way - the Wye Valley Railway,

the Severn and Wye Railway and the Forest of Dean Branch have

been quite well examined over the years. The Hereford, Ross and

Gloucester was covered in the June 2010 issue of Steam Days

magazine, which provided the interesting snippet on line ownership

around Grange Court. Cab Rides - Around the British Isles

- No. 16 (Cardiff to Birmingham) provides a driver's eye view

of the entire route on DVD, including the inside of Newnham Tunnel

(which is dark; what do you expect from a tunnel?). Devoid of

commentary, over twenty years old and from the cab of one of

the short-lived Class 155s, it makes an interesting historical

record which you can always try to watch in conjunction with

this webpage to see what's changed.

>>>Forest

of Dean Central Railway>>>

<<<Return

to Wye Valley Railway<<<

<<<Return

to Railways Department<<< |