|

|

||

|

|

||

|

When 1950 dawned only a handful of railway locomotives and coaches had been preserved - most of which had been saved because the Science Museum had been persuaded to take them or because the Great Northern had been fond of saving its heritage. Liverpool and Manchester No.57 Lion had scraped through as a preserved locomotive because it had done 70 years as a stationary engine and was now becoming a major film star courtesy of a rather liberal attitude to the 125-year-old locomotive from its owner, the Liverpool Museum. Meanwhile, the ex-London, Brighton and South Coast Railway locomotive Gladstone had been saved because the Stephenson Locomotive Society took a fancy to it. A couple of Scottish locos had managed to blunder through the war without being cut up. The Great Western had built a replica North Star and Tiny had inadvertantly slipped through the net to become the only original broad gauge engine. That was it. Meanwhile, in Mid-Wales, the only operating independent railway, the Talyllyn, was on its last legs and owned by an 82-year-old ex-Liberal MP who had promised to keep it running until he died. In summer 1950, he did so. Suddenly the future of the railway looked very bleak. As it is being mentioned in an article primarily concerning preserved railways, it is obvious that it was either the loss which kick-started preservation as we know it today or the first in a long line of heritage railways. With the owner dead, the manager obeyed the owner's will with relation to his paperwork. All the papers associated with his shop, his former constituency and his railway were taken to a corner of the Talyllyn's western terminus and unceremoniously burned. The original blueprints of the two locomotives, which had survived with the engines they showed since the 1860s, were destroyed. That was no matter, since it was expected that soon the locomotives would go the same way. No.1 Talyllyn had cracked cylinders, a leaking boiler, a rusty saddle-tank and life expired frames. She had only built up enough steam pressure to move herself last time she had worked - four years previously - because her boiler had been filled with oats, resulting in a strange smell of porridge lurking around the shed for a few days. No.2 Dolgoch was about to die of the same problems as Talyllyn, except she didn't have a saddle tank. By a strange quirk of fate, the original company had bought two locos from the same company within two years of each other which shared no common parts. But the "Old Lady" had put in a couple of years less work than her partner, and had a little while to go before she could no longer hold pressure in her boiler. The original coaching stock, last maintained properly in the pre-Adamite period, was creaked up and down the line with steadily falling passenger numbers whenever Dolgoch was healthy enough to work the train. The original track, half-mile a mile of which had been replaced using track from the Corris Railway (which had closed in 1948 and had no straight track itself, so the relaid straight stretch consisted of a series of dog-leg curves) had disappeared into the undergrowth some decades previously, although happily the locomotives knew where they were going and could just about get along without it. The widow of the owner had virtually no assets apart from a shop and this railway. Unfortunately, to realise the value of the railway she would have to close it first. Therein lay the problem. That required an expensive Act of Parliament. Further up the coast, the Ffestiniog lay moribund for want of enough money to arrange the closure process, which would have allowed it to salvage the scrap metal and pay off its debts. Happily for the good widow a group of mad railway people from Birmingham, led by Tom Rolt and Bill Trinder, who had been hanging around for some years now offered to buy the railway and run it as a going concern. Unable to believe their ears, the widow and her solicitor sold the railway to them for a song and sat back to see what happened. The first thing the preservationists did was try to get Dolgoch a new boiler certificate. Although they were expecting to be rejected, the inspector confirmed that the Old Lady was at no risk of blowing her boiler up (as she was unable to build up enough steam pressure to do more than limp up the line) and allowed them to keep running her. She worked the first ever preserved train on the first ever preserved railway in the world on Whit Monday 1951. But as Dolgoch was slightly less serviceable than a corpse and Talyllyn was worse the preservationists cast around and found the Corris Railway and its two locomotives. Brilliant! Another two elderly, unservicable machines with no common parts! |

||

|

||

|

They were bought for £30 the pair, along with wagons at 10s each and the brake van for £1. Once the fleet was moved to the Talyllyn, examination started. Corris No.4 (now Talyllyn No.4) was a basic machine from Leeds which needed a new boiler. The Hunslet Engine Co of Leeds, who had bought out the original builders, offered to replace it at cost. No.4 could be back in traffic for 1952. Corris No.3, meanwhile, was in full working order, because the Corris Railway hadn't used it so much. The Talyllyn, pleased with its luck, set to work. Talyllyn was dragged round into a hay barn next to the station adjacent to the railway's engine shed, and sat there gazing out at the surroundings and watching what went on. Dolgoch sat in the shed and kept quiet. The new No.3 was steamed with some difficulty, staggered out of the shed, was persuaded to couple to the coaches (which were 10 years older than it was) and ran around them in a grumpy unco-operative manner, steaming badly. It then hauled them into the station and the passengers got in, ready to start. No.3 moved off. It lurched, bumped and stopped. The crew got out and had a look. It had pushed the rails apart, and settled down between them. No.3 was returned to the shed in disgrace and Dolgoch told to wheeze up the line. She did. She continued wheezing up and down the line on increasingly heavy trains for the rest of the year. It became apparent, upon examination, that while both railways might have started at 2ft 3inch gauge, the Corris had fitted their locos with very thin wheels to let them get around the corners, while the Talyllyn had kept the original wheels and simply increased the distance between the rails at the appropriate moment. No.3 would be of no use until the track had been relaid. If Dolgoch failed before No.4's new boiler arrived, it would be porridge for Talyllyn again. Happily Dolgoch did not fail. No.4 entered traffic in 1953 and Dolgoch went away for a well-deserved overhaul. By the time she left her smokebox door was being closed every morning with the aid of bathroom sealant. Talyllyn departed shortly afterwards with a board proclaiming (in very bad Welsh) "I will return again". She did, four years later and after a lengthy overhaul, although certain modifications meant that she was not in a state which would allow her to haul a train. Happily by this stage the Railway had procured another locomotive - No.6 - and were able to use that on trains. It once again shared no common parts with the rest of the fleet and happily indulged in rock-and-roll at inappropriate moments. Nonetheless, the Talyllyn is now a prospering railway with 10 locos (6 steam, 4 diesel) all of which have no common parts. Curiously, the one most suited to the line, as well as being the smoothest rider and possibly the one that people would most like to cuddle up to at night, is the original member of the fleet. Talyllyn, however, has a vicious bite for those who get too close, is the loco which cleaners are most likely to fall off and has a strange habit of covering herself in soot when you have just finished cleaning her. |

||

|

||

|

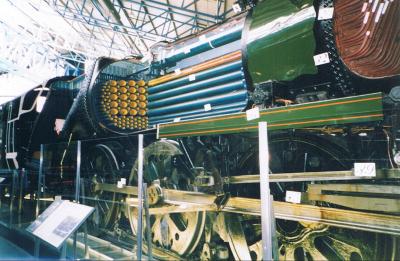

Inspired by the Talyllyn Railway, filmwriter T.E.B. Clarke produced a script for Ealing Studios about a railway running to a little village called Titfield which was going to be closed and so the local residents took it on and ran it themselves. Not everything goes according to plan and the GWR tank engine is written off, so the residents have to borrow the railway's original locomotive, Thunderbolt, from a local museum. The task was to find a suitable locomotive to play Thunderbolt. It had to be a very old locomotive which could steam around under its own power. Happily Liverpool Museum had one, and so Lion was taken down to the recently-abandoned Camerton to Limpley Stoke branch near Bath and used in filming. She also put in an appearance at Bristol Temple Meads, though railwaymen from the time recall her as a wheezing, underpowered and life-expired beast barely able to move herself and so she probably didn't do it under her own power. It was one of those rare occasions when a locomotive worked on an active railway which was younger than it was. Although in the film it was the Great Western engine which was written off and the old engine which worked without incident, the filmakers nearly got it the other way round, returning the tank engine to British Rail undamaged, but accidentally forcing Lion's tender over the locomotive's frames, leaving a large gash which can still be seen today, ending her film career and nearly destroying a priceless exhibit. The Titfield Thunderbolt, released in 1953, helped raise awareness of the Talyllyn and is a cult film in railway circles - as well as featuring, in glorious Technicolor, a brand new bus, a smart lorry and a working steam roller, all of which look as obsolete as Thunderbolt now nearly 60 years on. At the same time the Reverend Wilbert Awdry visited the Talyllyn. He had been writing books for his young son Christopher about a locomotive called Thomas and his friends Edward, Henry, Gordon and James. Wishing to widen his scope, he wrote four stories about the adventures of a little loco called Skarloey and his friend Rheneas, who had been taken away to be mended leaving Skarloey alone with two new engines. At the end of the book Skarloey gets to pull a passenger train and so is sent away to be mended as well. Awdry's creation gives an impression of a run-down railway with two old tired locomotives and two new ones - one grumpy to have left home and one keen to meet a new world. Apart from the fact that it is rather more realistic, it is not a bad impression of the Talyllyn's early days. The Ffestiniog came next in the preservation stakes, when the original company was bought out by millionaire's son Alan Peglar and his bunch of friends. Their first locomotive move was, in contrast to the Talyllyn's wheezing Dolgoch going halfway up the line and back, a little experiment with a First World War veteran built by Simplex. The rather basic petrol locomotive was cleaned of sand and moved backwards and forwards a few times, just to show that it could be done. Passenger services hauled by said Simplex along half a mile of track between Porthmadog and the sheds began in mid-1954. 1955 saw them taken over by No.2 Prince. No.1 Princess has not worked for the new company, being used as a static exhibit in the railway's museum. Prince is arguably too small for the railway's heavy trains - something recognised back in the 1870s when the original locos were in their teens - and rarely gets to the top end of the line these days. Standard gauge was the next step. So far the railways preserved had been the world's first narrow gauge line built for steam traction (previously they had been worked by horses) and the world's first narrow gauge railway to use steam locomotives, bogie coaches or steam locos on bogies (also called Double Fairlies - the line now has three and is very fond of them). So the task was to find a truly historic railway to save for posterity as the world's first standard gauge preserved railway. Can you think of one? In 1960 two historic railways were really under threat. The first was the 1807 Swansea and Mumbles Tramway, which was shut by a bus-mad Swansea City Council. Only one tram was preserved - No.2, which was moved to Leeds. Leeds, home of the Hunslet Engine Company, which was looking at the fourth diesel locomotive ever to run in Britain (LMS No.7051) and wondering what to do with it. In early 1960, courtesy of some students at the University of Leeds and their lecturer, Dr. Fred Youell, it found itself paired with the exiled electric tram on the first train to run on the first standard gauge preserved railway. Which, by immense coincidence, had also pioneered the concept of preservation itself in the early 1820s when it "preserved" (and subsequently scrapped) one of the first commercial steam locomotives in the world. It was the Middleton Railway. The world's first railway, 202 years old, was preserved for posterity. So it thought, anyway. |

||

|

||

|

The problem with old industrial railways is that they have no passenger stations, so you have to immediately break the preservation idea by changing the line entirely by installing platforms and passenger facilities. Then you have the issue of industrial railways running through run-down areas, so things get vandalised - such as a mine which would have made a jolly good visitor centre had the locals not vandalised the thing until it fell down and stolen the track. One thing which the Middleton did manage to retain was its propensity for scrapping rare and valuable preserved vehicles, demonstrated when it burned the body of the Swansea and Mumbles tram following a particularly bad vandal attack. While Swansea was and remains rather cut up about this, it must be remembered that the tram was exiled by a city which, a few years previously, showed no inclination towards saving more than a decapitated cab off one of its trams (which it still has). The Middleton also kept some freight traffic and continued to work based on its original Act of Parliament. Just when people were starting to ponder the value of this, the Ministry of Transport announced the route of the new M1 motorway into Leeds. It was going to cross the Middleton and slice it in half. The Middleton protested and was told to get lost. Dr. Youell began waving the Act of Parliament around, but wasn't taken terribly seriously at first. However, after a while it became apparent that the Middleton had no intention of going away but was willing to compromise. Dr. Youell would accept that the motorway did have to be built and would settle for a level crossing if needs be. The idea of a brand-new six-lane motorway (then carrying traffic unconstrained by speed limits) being brought to a grinding halt so some students and mad academics could run a tatty 7051 over it at 15mph on a relic of the Georgian era (when the Middleton was built the USA was still a British colony) did not appeal in the slightest to the MoT, who agreed to provide a bridge over the railway. The railway is still there today. The motorway is now the M621 and the M1 goes somewhere else. The liklihood remains that the Middleton, which is still open and carrying passengers with trains often hauled by septogenarian 7051, will outlive the motorway by a considerable margin. In 2008 a collection of Members of Parliament signed a congratulatory notice for the Middleton Railway to celebrate its 250th birthday, which can be taken as an apology for the Government's earlier despicable behaviour and a general cheer at the power of an Act of Parliament (though the Act itself was repealed as part of a general tidy-up of old laws in 1978). Meanwhile, re-opening to much wider awareness (being much closer to London) a few weeks after the Middleton was the Bluebell Railway. Based at Horstead Keynes in Sussex, the railway was proud to have never been worked by a diesel and began building up a large fleet of steam locomotives of various historic designs. Passenger numbers rose and the Bluebell, while not a large railway, is certainly one of the leading lights of preservation. Then came the moment when outside politics began to truly affect the heritage world. Dr Beeching took over British Railways and in 1963 issued a report. 6,000 miles of railway were shut and the entire steam locomotive fleet withdrawn and disposed of, mostly to private scrapyards. Enthusiasts all over the country gazed on in horror and wondered what they could do. Then they remembered Gladstone, the Talyllyn and the Bluebell. They leapt into action. For the first time, here was an opportunity for them not just to watch the trains going past, but to have the trains they wanted in the condition they wanted on railway lines all over the country. British Rail, acknowledging that something had to be preserved, drew up a list of locomotives for a National Collection. This list included several locomotives which had already been preserved and only featured one of the LNER's big express engines. (This was one more than the number of the LMS's big express engines which got into the line-up). Only two non-steam locos entered preservation at this point - little NER electric No.1 and a big blue diesel with large noses and cream stripes called DELTIC. The big LNER express engine was inevitably Mallard. Bullied was well represented - Winston Churchill was officially preserved as was, Ellerman Lines was taken in and sectioned (bits were cut off so people could see how it worked) and the first of the Q1s was also saved for posterity. The first of the Great Western "Star" and "Castle" classes were saved for posterity along with a couple of pannier tanks. The LMS was represented by a couple of survivors from the Midland Railway and the first of its successful fleet of freight locomotives, the "Black Fives". The Science Museum looked at the last big new prototype steam loco, No.71000, and decided that it was sufficiently groundbreaking to save the left-hand cylinder. The rest of the loco joined withdrawn Great Western, Southern and BR engines in a scrapyard in Barry, South Wales. |

||

|

||

|

LNER fans, feeling under-represented, saved three further A4s for the UK - Sir Nigel Gresley, Union of South Africa and Bittern. Dwight D. Eisenhower was sent to the US and Dominion of Canada now resides in Canada. Class leader Silver Link unfortunately went to the cutter's torch. Alan Peglar purchased A3 Flying Scotsman and an extra tender and arranged a mainline contract which would keep it on the mainline until 1972. A television appeal saved A2 Blue Peter for preservation. A campaign to save St Mungo, the last of the A1s, fell through and the loco was cut up, destroying forever hopes of lining up all four types of great East Coast express steam locomotive. The LMS benefitted from a great railway preservationist called Billy Butlin, who took Royal Scot and Duchess of Hamilton for display at his seaside resorts. Alan Bloom, owner of a garden centre at Bressingham in Norfolk (bordering on Suffolk), purchased another Duchess, Duchess of Sutherland, and subsequently added Royal Scot to his collection. Duchess of Hamilton, after much hopping around, ended up at the National Railway Museum. City of Birmingham was acquired by Birmingham City Council, and today looks out from its plinth over the remains of Birmingham Curzon Street station. Two of the "Princesses" also scraped into preservation, although hardly with homes which matched their royal associations (6201 Princess Elizabeth, named after the woman who later became Queen Elizabeth II, spent its early years in preservation on a stretch of track next to a brewery). One LMS loco was eventually saved by the scrapman who bought it on the basis that it looked like it was worth keeping, and is now named Alderman S. Draper in his memory. The Great Western saw several smaller tank engines saved directly from BR, along with No.6000 King George V, the first of the Great Western's express locomotive fleet. Various "Castles" and "Halls" escaped scrapping and Olton Hall even got to become a movie star as Hogwarts Castle, much to the irritation of Great Western purists, who thought that a "Castle" should have got the role ("Castles" were named after castles; "Halls" after halls. Unfortunately so many "Castles" were built that they eventually ran out of castles to name them after). Thirteen panniers had found themselves working maintenance trains "after hours" for London Transport and just over half of these would be preserved. About 100 Great Western locomotives of various shapes and sizes found themselves in a scrapyard in Barry, South Wales. The Southern had already scrapped most of its smaller steam locomotives and only about 15 remain. What couldn't be electrified quickly and wasn't shut was dieselised in the early 60s. A row over electrifying the line from Basingstoke through Salisbury to Exeter, Barnstaple, Plymouth and Padstow saw it taken away from the Southern Region and given to the Western. The former Great Western Railway supplied its own traction and shut most of the line. This allowed the Southern to ditch about half its express passenger fleet, the rest of which was retained for Waterloo to Bournemouth/Weymouth trains. In 1967 the axe fell on the last big steam operation in the country, leaving a handful of LMS and BR steam locos in the North-west to work into 1968 on a few trains. Bullied's express locomotives were sent to the only place still buying in more engines - a scrapyard in Barry, South Wales. |

||

|

||

|

One Southern loco managed to completely disappear when the owner of the last South Eastern and Chatham Railway (this dates it to being over 50 years old by this point) O1 locomotive found himself in some financial difficulties. The locomotive was despatched to a field near the East Coast mainline, where it lived with a collection of traction engines for 30 years. Occasionally traction engine enthusiasts came to look. None of them knew what an O1 was and so paid it no attention. When its identity was eventually revealed in 1996 there was some surprise that it had stayed hidden for so long, with its guardian not even knowing if its owner was still alive. It now works on the Bluebell Railway. The BR locomotives came through things very badly. The first and last were officially saved for preservation, although the first was nearly broken up on the basis that it wasn't in a fit state to preserve. It is currently in hiding. The last, Evening Star, worked for 5 years, twisted its frames in an accident and is now at the NRM (although there are occasional conspiracy theories as to whether that is the actual last engine or an imposter). A few freight engines of various shapes and sizes got to enter preservation. Of the last three steam locos to run on BR, one was preserved for use on a heritage line, one was used in the film Virgin Soldiers and broken up on set and the very last, Oliver Cromwell, went to Bressingham - where Bloom got to watch it coming under a nearby railway bridge and suddenly realised that it was a big engine, a low bridge and nobody had thought to compare the measurements. Cromwell scraped underneath and did not work another train for 40 years. The only steam loco left on BR was Flying Scotsman. In 1970 Peglar upped and took it to the States for a massive show-off and to make lots of money. He returned a year later, completely penniless. Scotsman remained in the States. She was being held as a guarantee and while scrapping was probably unlikely it was entirely possible that she would never return to the UK. Preservation also came to buildings and structures around the railway. In the early 1960s the original London terminal, Euston, was on the verge of being electrified. It was a massive, rambling place, centring on a Great Hall used for big events and a huge Doric Arch obscured from the road by the station's hotel. Platforms were of varying lengths depending on their age and 16, 17 and 18 were stuck off down a corridor somewhere round the back. BR decided to tidy the place up by demolishing it and building a new station with an airport style concourse and the platforms under a low roof with offices on top - apart from 16, 17 and 18, which were to go in a big warehouse somewhere round the back. There was what passed in the 1960s for a massive protest with agitated letters being sent to BR. The Prime Minister Harold Macmillian said something about Britain needing to look forwards and the station was demolished. The stones from the Arch were used for flood protection in East London. With the purpose of the flood protection now largely negated, it is a generally popular idea that the stones should be gathered up and put back together again in front of the station. Meanwhile, the slightly taller building at Birmingham Curzon Street survives (for a general idea of the scale of the thing) and the little gate lodges at the entrance to Euston station, listing the many places served by the London and North Western Railway, are still intact, albeit somewhat out of place. Euston was duly reborn as a very modern (unattractive) building. Shortly after the protestors got a chance to have another go. This time the stakes were higher - the huge Gothic heap that was St Pancras, the Midland's London terminus, was due to be demolished. Protests began and protests continued. The Poet Laureate, John Betjeman (a noted fan of idyllic history), stood up in support of the station. A different Prime Minister, remembering something about a broken promise to get rid of Beeching, probably helped. St Pancras moved from being a doomed structure to a Grade I listed building - no major alterations can be carried out. BR left the station alone. Slightly too alone - services were reduced, maintenance cut and cleaning abandoned. The vast St Pancras Hotel was left derelict. But the station was safe from demolition. The preserved engines and associated coaches needed railways to run on, and early ones included the Severn Valley, the North Yorkshire Moors, the Isle of Wight, the Great Central and the South Devon. This last had been closed by Dr Beeching in 1963, but he was persuaded to return in 1969 and re-open it. He cheerily commented that he expected that it would be one of a group of successful heritage railways, but that they would only be successful because of their comparative rarity. |

||

|

||

|

Beeching's comments have remained as a cloud of doubt at the back of people's minds ever since - oddly, since they disagree with him entirely on his basic view that there were too many railway about to begin with. When these comments were made there were only about two dozen heritage lines in the country. Now there are nearly two hundred. There is always a fear that the market will be overloaded and too many railways will spread too few visitors too thinly. Most railways doubled their size in some way or another after the 1990s recession and were uncertain how they would ride the next, but most of them have come through well enough. The growing industry needed a growing number of locomotives to haul its trains. No more would come from BR. They'd scrapped their stocks and were turning to the more unreliable examples of the diesel fleet. Most of the very early prototypes had gone. This was being regretted. Diesel preservation, although very much in its infancy, scored in 1972 when the Western Region's D6319 became the first diesel locomotive to be purchased for preservation. Unfortunately, by the time the purchaser arrived at Swindon to collect the recently-overhauled locomotive, which was the last of its kind, all that remained was a pile of scrap metal. Diesel preservation was not getting off to a good start. British Rail was very apologetic and, in one of those kind gestures which the organisation was occasionally good at, offered the pioneering preservationist the opportunity to buy another loco for the same price. He selected one of the locomotives which had replaced the "Castles" - "Warship" class D821 Greyhound. The "Warship" was the first mainline diesel to work in preservation (as opposed to diesel shunters; lots of them had been preserved already). It has recently undergone an overhaul and normally lives on the Severn Valley Railway. With the Western Region being engaged in scrapping its entire diesel fleet - for reasons which need not concern us, although they were something to do with the locos being too light, too reliable and too capable compared to the diesels used on other regions, and so urgently in need of being replaced with something more standard and slightly inferior - diesels were hardly in short supply for preservation. About 15 slipped through the net at this point and were later joined by another 15 which reached preservation via industrial service. Two also found themselves at a scrapyard in Barry, South Wales, along with one of a fleet of unreliable Scottish diesels. With the steam locos out of the way BR rounded on several prototype fleets and a couple of large classes of failures which they had wanted to be rid of for years. Spotters who left the hobby in the mid-60s and came back in the mid-70s wondering how those new diesels which had replaced their beloved steam engines were getting on found that they had completely disappeared. After some searching they found a couple in the Barry scrapyard and told the diesels what they thought of them. While Barry built up a collection of interesting and historical asbestos-filled rust-buckets in the former dock area, British preservation turned to Flying Scotsman, still exiled in the US. Its decaying condition meant that a buyer was needed imminently. It was acquired by builder William McAlpine, repatriated and overhauled. Its original mainline ticket had expired, but British Rail was more amiable than they had been immediately after the demise of steam and the ban on steam locomotives hauling trains on the mainline was lifted in 1971. Great Western locomotive King George V became the first steam locomotive to haul a train on the mainline since Flying Scotsman had crossed the Atlantic. Now Scotsman returned and, overhauled and without its second tender, the locomotive soon began hauling specials on the mainline again. McAlpine even made a trip to Australia, where it met exiled (and since repatriated) Great Western locomotive Pendennis Castle and made the longest-ever non-stop journey by a steam locomotive. The locomotive managed to return intact and with the same owner. Now everybody wanted their own locomotive and only one place in the country still had good stocks of steam locos. Woodham's Scrapyard in Barry, South Wales, now had a collection of 220 of the things but no intention of scrapping any of them. This was a purely business-based decision. Steam locomotives yielded a lot of metal but were hard to cut up. Diesel locomotives yielded less but were slightly easier. Wagons yielded several tons but needed virtually no work at all. BR had built a tens of thousands of 16ton mineral wagons for carrying coal and stone, almost as many flat wagons for carrying small goods containers and nearly 4000 standard brake vans. Nearly all of these were now surplus to requirements and, while the containers made good storage sheds (and can be seen fulfilling this capacity all over the country), none of the wagons or vans could be found any further use. There was good money in scrapping them. So Woodham scrapped them and was quite happy to listen to offers to buy his intact steam locos at scrap value (a business which saved on scrapping them and was therefore more profitable). All that was needed was permission from BR, which was granted in 1972. This was not an opportunity for locomotives to stream out of the yard into preservation. The first to depart was a typical example of the Midland Railway's "small engine" policy - a Fowler-designed 4F tender engine. Around 120 locomotives left over the next 8 years in varying conditions, but mostly in fairly good nick, having spent less than 10 years in the salty air blowing onto the former Works and Docks of the Barry Railway. All of these locomotives were steam powered. |

||

|

||

|

BR began to officially recognise the heritage of the railways as a good way to improve their own standing during the 1970s. In 1971 GWR No.6000 King George V brought steam back onto the mainline with a railtour sponsored by Bulmer's Cider of Hereford. In 1975 the 150th anniversary of the Stockton and Darlington Railway opening was celebrated by a massive Open Day at Shildon and a parade along the mainline featuring a wide array of steam locomotives plus BR's pride and joy from the time - the High Speed Diesel Train prototype set. Painted white and with airconditioned coaches, it looked very out of place compared to the various steam locomotives, which were mostly in black. (The LNER had celebrated the 100th anniversary of this event by steaming the original Locomotion No.1 - by 1975 this was too risky and a replica deputised.) In 1980 the Liverpool and Manchester's 150th birthday was celebrated with a parade at Rainhill, centre of the Trials all those years ago. Unfortunately the replica Rocket derailed, with the result that it missed the parade and the replica Sans Pareil had to wait in the yard for Rocket to be tidied up and then bring up the rear. A nicely overhauled Lion led proceedings instead. At the back was the prototype Advanced Passenger Train set; being an electric train on an unelectrified line it had to be pushed ignonimously by a diesel. The 1980 event was not as well patronised as the 1975 one and no such event has been run since. Closing the line for a day would now be out of the question anyway. There were fewer passengers then. In 1980 a shortage of suitable wagons saw Woodham turn his torch on the locomotives. The last two North British Locomotive diesels had been residing in his yard for 12 years; these were now broken up and two fleets rendered extinct. Two steam locomotives then bit the dust. It provided the necessary push to get another stream of departures, quickly followed by another incoming stream of the apparently limitless stocks of 16ton mineral wagons. This allowed Woodhams to continue scrapping wagons, selling locos and making a sufficient profit to move into leasing industrial units (small brick and steel buildings for running a mini-factory in - mostly located alongside Barry No.2 Dock). Dai Woodham announced his retirement in 1989 and the remaining locomotives - which had now been disintegrating in the fresh sea breeze for 20 years - were pushed out of the yard. Of the final 12, ten were taken by the local authority for long-term restoration and the other two, which were both of the same type (GWR "Small Prairies") were bundled together to create a cardboard cutout (5538) and a kit of parts which might be restored (5553). 5538 was placed on Barry Island seafront and enjoyed a further ten years in the bracing sea breeze before getting moved to spend the next eight years in a slightly more sheltered corner of the island. It is now being restored elsewhere. One of the Barry Ten, as the local authority's fleet is known, has now been sold for rebuilding. Two have been taken away for dismantling for spares and to recreate lost classes. The rest of the fleet are still dumped in a shed in Barry with a doubtful future. Because Woodham's bought batches of locos, some fleets have a large number of survivors while others, withdrawn at about the same time but sold elsewhere, are extinct. Only one ex-LNER loco found itself in Barry, probably by accident. Two GWR "Kings" also ended up there, when they were taken to Cardiff and sold to a scrap merchant in Neath, near Swansea, before it was realised that they were too heavy to make the trip and they were switched to Barry. Twenty-eight of Bullied's express locomotives finished up in Barry, representing most of the fleet which survived to the end of Southern steam. This creates the problem that, while spares are not too much of an issue (more of these locomotives survive than were built of many diesel fleets), the spares are occasionally obtained by stripping unrestored unfunded examples of the fleet. Owning a locomotive should not be confused with preserving it. The former is fun, if occasionally brutal. The latter ends up with the the paradox as to whether you stuff it so the original bits survive and can be studied or restore it so people can enjoy see it running. (After about 80 years, you have to opt for one or the other. The Talyllyn Railway runs both original engines, but none of the bits of metal currently in No.1 Talyllyn were delivered to the railway in 1864. The frames were replaced fairly early on and have since been extended, the loco is on its fourth water tank, the cab is a later addition and the boiler and cylinders were replaced with new ones through sheer necessity in 1954; they probably weren't the originals.) Woodham's also ended up with 11 of Riddles's mixed traffic Standard 4 tanks - capable machines and the ideal size for any steam railway - along with 11 "Small Prairies" and 11 examples of Riddles's criminally underused masterpiece - the heavy freight "9F". Ten of these have entered some form of preservation, although one is now a member of the Barry Ten. That last of the prototype steam locos, 71000 Duke of Gloucester, had been written off as irrepairable in 1965, with one cylinder in the Science Museum and the other removed to keep the loco balanced. It had not been regarded as a big success and nobody in officialdom saw any reason to preserve it. Yet in 1974 it was purchased from the scrapyard and the long overhaul process begun. Many donations and much measuring of the original cylinder allowed the locomotive to be rebuilt. A few modifications were carried out, particularly involving a larger chimney. When steamed, it steamed perfectly. Capable, powerful and speedy, the locomotive now runs a large number of railtours each year with few issues. The end of the 1980s also saw British Rail persuaded to get rid of a little indulgence - the narrow-gauge steam-operated Vale of Rheidol Light Railway from Aberystwyth to Devil's Bridge. The three locomotives and 16 coaches had been running around in standard BR blue as the only BR passenger steam operation since 1968, but they were now privatised, with the lucky winner being the Brecon Mountain Railway. This comparatively small affair, running a few miles of narrow-gauge railway on the trackbed of the Brecon and Merthyr Railway above Merthyr, brought two of the locomotives down to South Wales and carried out major overhauls on them at their Pant workshops before the two railways parted company in 1996. The Vale of Rheidol likes to ignore its blue years, on the basis that nobody liked them (an argument disputed by punters who remember blue and are not mad Great Western people), and has painted its three locomotives in heritage liveries. Currently No.7 is under overhaul and Nos. 8 and 9 are in green. Diesel No.10 is a grimy maroon and is not used on passenger trains. Nos. 1 and 2 were the original locomotives, to a similar design to their successors but with no common parts, No.3 was a shunter on the docks branch at Aberystwyth and Nos. 4 to 6 never existed. |

||

|

||

|

Diesel and electric preservation also grew. The LNER's Woodhead Route had closed to passengers in 1969 and the EM2 locomotives used on passenger trains had moved to the Netherlands. The EM1s had struggled on to 1981, after which one was preserved by the NRM. When the EM2s were withdrawn by Netherlands Railways in 1986 preservation went slightly better and three of the six which worked on the Continent were preserved - two here and one there. The Dutch survivor has hauled special trains on the mainline and the doyenne of the fleet has returned to the Netherlands to haul a few specials as well. The original West Coast electrics were withdrawn in 1990 and one of each of the five types slipped into preservation. The surviving AL1 was bought from service, one each of classes AL2 and AL3 were acquired from the scrap lines at Crewe, the doyenne of the AL4s had been taken by the NRM as a temporary exhibit (it was finally deemed to be preserved for the long-term in 1995 when a quick stock-check confirmed that it was the last North British Locomotive Company modern traction mainline locomotive in existence) and one of the last AL5s was preserved in full working order in 1991. Unfortunately it rapidly transpired that it and all the other examples stored at Crewe had been sabotaged and so it was taken back to BR, who swapped it for the only fully operational example left. Its operational status proved to be entirely academic, since none of these locos has run in preservation. With Barry emptied by 1990 all the big challenges seemed to be over and some men in a pub instead bewailed what had not been saved. Top of the list came the Peppercorn-designed A1s. There were some cheery suggestions about what would happen if a new one was built. They looked at the diagrams. They thought about it. They looked at prices. They started an appeal to build a new one. LNER express locomotives dominated the preservation headlines after that, with occasional interventions from Duchess of Hamilton. In 1994 the last A2, Blue Peter, reached 140mph while going nowhere, writing off the pistons and motion and creating some interesting holes in the rails. Another appeal on the Blue Peter TV programme was needed - should this programme be axed the A2 would probably be stuffed and become a static exhibit (although it already has been and the programme is still on air, so if the BBC do ever want to axe it that shouldn't affect Blue Peter's career too much). The last of the LNER B12 fleet - a medium-sized locomotive for the Great Eastern network - was despatched to Germany for overhaul. The loco - which had been in preservation for 30 years but had never worked a train during that time - was rebuilt at Meingein Works, on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain, alongside steam locomotives still in daily service. In 1996 William McAlpine decided he wanted out on Flying Scotsman and sold her to Dr. Tony Marchington. A minor millionaire, Marchington relished the challenge and promptly began a massive overhaul. Scotsman steamed again in May 1999 and handled a number of mainline specials. Meanwhile the NRM suggested that the bathtub could be put back on Duchess of Hamilton for a suitably large fee and the locomotive was withdrawn. Work began in 2006 and has now been completed. Scotsman proceeded nicely until financial issues began in 2003 and the locomotive was placed on the market in 2004. It was sold for £2.2million to the NRM later that year and, saved for the nation, began draining financial resources. Although it is unlikely that the locomotive can be entirely blamed for the current financial crisis, it only managed half a summer of York-Scarborough specials before it had to be withdrawn for an overhaul. Its place in the "Flying Scotsman" section of the museum has been occupied by Great Northern Stirling-designed "Single" No.1 and BR "Deltic" 55002, both of which worked the route of the famous train but neither of which looks in the slightest bit like a London and North Eastern Railway A3 express locomotive. After both found better things to do the slot was even taken by the surviving prototype High Speed Train power car - an exhibit which was then realised to be deserving of its own section and a return to full working order. There was some considerable debate as to whether Scotsman should get a new boiler and whether it should get a new coat of paint. The more important questions - whether it should run again or if a replica should be built and why Marchington's perfect in-depth overhaul completely failed to secure the locomotive's future - have not been answered. Meanwhile, Marchington was declared bankrupt in 2005. The frames have now had 7 owners and 5 of these (the LNER, BR, Peglar, Marchington and the UK) have suffered financial difficulties after taking them on. McAlpine pulled out before doing a major overhaul and the GNR never got to run the loco. One may consider them lucky. Locomotive overhauls also began to produce some interesting facts which nobody had expected. Volunteers at the preserved engine shed at Tyseley in Birmingham were rebuilding Great Western "Hall" No.4983 Albert Hall when they began to notice that most of the bits were stamped with the number of long-scrapped Rood Ashton Hall, No. 4965. When it was found that this was not just a few bits but every part of the engine other than the boiler, some examination of the practices of Swindon Works began. This revealed that 4983 had suffered from problems with its frames in the final days of its life and had eventually ended up the works with a newly overhauled boiler alongside 4965, which had a dead boiler but good frames. Normal procedure would have been to swap the boilers and mark the paperwork accordingly, but with both locos soon to be scrapped anyway and a lot of paperwork and inspections being involved in officially swapping boilers it was decided to hide it, and so everything other than the boiler was swapped instead, which has much the same effect but involves less paperwork. The boiler and nameplates of 4965 and the frames of 4983 were broken up, a clerk told to record the demise of 4965 and the hybrid put back into traffic as Albert Hall. Two years later it was withdrawn and despatched to Woodham's of Barry. By the time the preservationists discovered this little switch in 1998 the loco had been Albert Hall for most of its life and new nameplates had been cast, but it was returned to the identity of the frames and now runs as Rood Ashton Hall. |

||

|

||

|

In 2004 the NRM opened a new site at Shildon on the Stockton and Darlington Railway so less significant exhibits (the experimental Advanced Passenger Train, a certain blue prototype diesel with cream stripes called DELTIC, North Eastern electric No.1, Locomotion No.1 and other such animals) can be displayed despite being off the main site. Some NRM exhibits, such as Oliver Cromwell, have also been stored at other locations, although Cromwell's time at Bressingham did not go entirely happily. When the NRM asked for it back to commemorate 25 years since the end of BR steam - as Cromwell worked the last train - Bressingham said it was on "indefinite loan" and did not have to be returned to York. Possibly Bressingham was upset as the decision to overhaul the engine and use it on the mainline was presented as a done deal and Steam Railway magazine had been told before the locomotive's guardians. It worked its first train since the end of BR steam in August 2008, exactly 40 years to the day after the last one (a commemorative special). There was another first since the 1960s in August 2008. At the beginning of the year the A1 Steam Locomotive Trust had organised construction of their new A1's boiler at Meingein Works in Germany. Once finished it was transported to Darlington, where the rest of the locomotive was essentially complete. The boiler was slipped into place and the loco painted. Suddenly what, a couple of months previously, had been a half-finished engine was steaming up and down the siding outside its shed and being broadcast live to the nation. The first runs took place on the Great Central Railway in Leicestershire, which allows locos on test to run at up to 60mph and therefore show off rather more. It caused massive traffic jams on the single-track lanes providing access to the intermediate stations of Quorn and Rothley. Tornado marked the beginning of a very satisfactory autumn where it seemed that the country's youngest steam locomotive had joined the ranks of A-list celebrities. Unfortunately the locomotive turned down all offers of interviews and the people involved consisted of the very elderly widow of the designer and a bunch of men in their fifties. It is no longer quite such a craze but has helped get the railways some far more positive press, at the expense of a number of trespassers during its mainline runs. At the time the BBC made a documentary about it, but much greater coverage was achieved with a starring role in Series 13 Episode 1 of Top Gear, where Jeremy Clarkson acted as the fireman. Clarkson seemed to be quite surprised that it was limited to 75mph and enquired about the liklihood of being caught on a speed camera. Railways do not have speed cameras - they have a box recording every second of the journey instead, which people occasionally look at. The next step is a line-up of the East Coast express locomotives. The principal target is to line up the "Pacifics" - the sole examples of A1 (operational), A2 (stored but intact), A3 (in bits and unlikely to be reassembled soon) along with one of the four A4s - probably the stuffed Mallard. After that there is the opportunity of lining up an example of each express locomotive to work the line since 1890 - the Stirling Single, an Ivatt Atlantic, the four Pacifics, a Deltic, a High Speed Train and a Class 91 - although all the HSTs and Class 91s are busy handling normal services. |

||

|

||

|

Coaches and wagons have had rather different fates to the locomotives. The Talyllyn has all of its original coaches, but this is rather unusual. Some preserved lines, like the Ffestiniog, have built replicas. The Middleton seems to have rebuilt goods vans. The Island of Wight Steam Railway and the Bluebell both have good collections of ex-Southern Railway vehicles and the West Somerset and Severn Valley have good rakes of ex-Great Western stock. The North Yorkshire Moors and North Norfolk Railways have some rather splendid teak coaches from the London and North Eastern Railway. Everyone else has to make do with ex-BR Mark 1 coaches - a standard vehicle which looks suitably outdated. These vehicles can then be painted in whatever livery the operating railway wants (blood and custard, chocolate and cream, all over maroon, teak, green or blue and grey) but invariably have 1970s interiors. Meanwhile the Bluebell Railway has unbent enough to find room for a diesel in its fleet, generally working construction trains on the East Grinstead extension, and even accepted the donation of an ex-BR electric commuter train. This stayed just long enough to announce its presence and then moved to the former London and South Western Railway workshops at Eastleigh, near Southampton, where a similar unit is being overhauled to mainline standards. While the units no longer comply entirely with health and safety restrictions, due to them being of the same body design (Mark 1) as the coaches working on preserved railways, there are still hopes that arrangements can be made for them to work mainline. After all, since the mid-1990s a slim-line diesel train which once worked the Hastings to London Charing Cross route has been ambling around with its equally non-crashworthy body on various routes, generally filling in for an absent train or covering extra services, and it has managed to stay on the mainline without too many problems. So that is preservation. The Middleton celebrated 50 years of preservation and 252 years in existence in 2010. Swansea has also made funny noises about bringing back the Swansea to Mumbles Railway. It would be nice if the two briefly joined forces and built a new body for the still-intact wheels, bogies and motor of the Swansea and Mumbles tram. It wouldn't fit under the M621, but it would fill another one of those gaps in preservation... |

||

|

|

|

|

|